The ostrich feather industry in South Africa, particularly in the town of Oudtshoorn, played a fascinating role in global fashion and colonial economics during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This period saw the rise of ostrich barons who amassed great wealth from the lucrative trade in plumes, fueled by insatiable Victorian and Edwardian demand for feathered hats and accessories.

At its peak, South Africa supplied 85 percent of the world’s ostrich feathers, transforming the Little Karoo region into an unlikely center of luxury goods production. The town of Oudtshoorn became known as the “ostrich capital of the world,” with grand mansions built from feather profits dotting the landscape.

The ostrich feather boom was not destined to last, however. Changes in fashion trends, the advent of the automobile, and the economic upheaval of World War I led to a dramatic crash in the feather market. This collapse had far-reaching consequences for South Africa’s economy and the fortunes of those who had built empires on ostrich farming.

The Lustrous Legacy of Ostrich Feathers

Ostrich feathers played a pivotal role in shaping fashion, trade, and colonial economies during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their allure captivated the world, sparking a global industry that would leave an indelible mark on history.

The Ostrich Feather Boom

The ostrich feather trade experienced an unprecedented boom in the late Victorian era. South Africa, particularly the Little Karoo region, became the epicenter of this burgeoning industry.

Farmers began breeding ostriches on a massive scale to meet the insatiable demand for their plumes. The industry’s rapid growth led to the rise of “ostrich barons,” wealthy landowners who amassed fortunes from the trade.

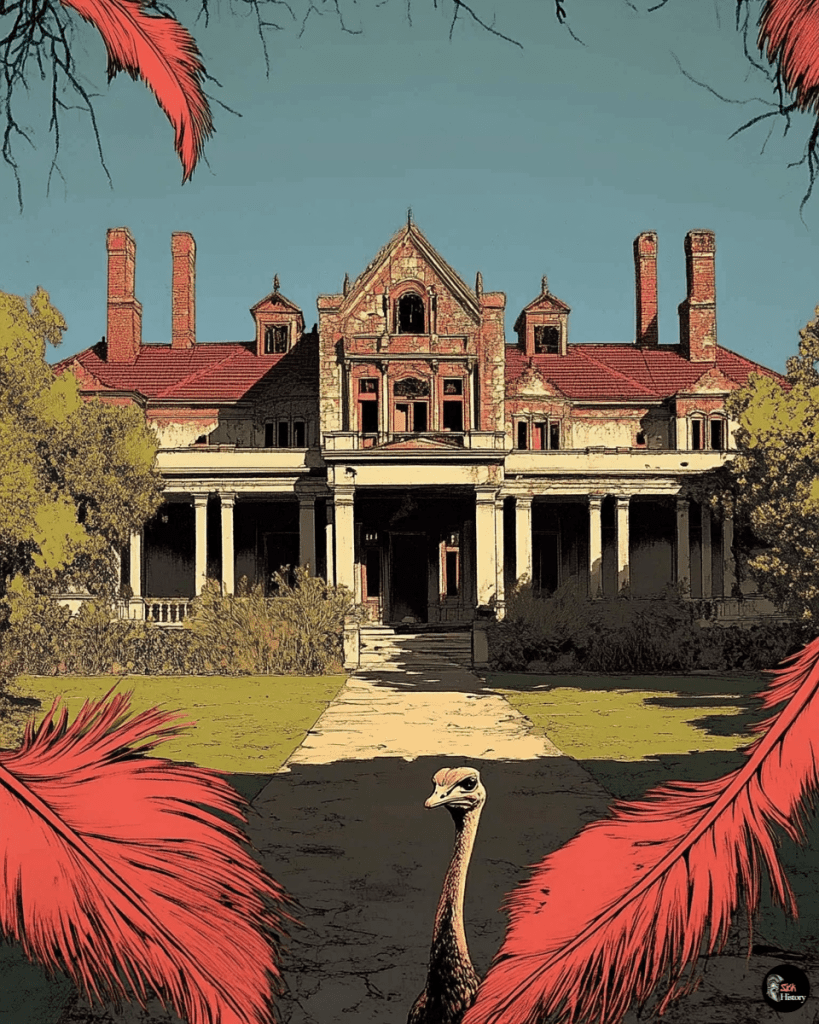

These entrepreneurs built opulent mansions, known as “feather palaces,” showcasing their newfound wealth.

The boom wasn’t limited to South Africa. Enterprising farmers in the United States and other countries also entered the market, setting the stage for fierce competition.

Edwardian Fashion and Luxury Demands

Ostrich feathers became synonymous with luxury and elegance in Edwardian fashion. Ladies of high society adorned their hats, gowns, and accessories with these prized plumes.

The feathers could be dyed in a rainbow of colors, adding versatility to their appeal.

Paris, the fashion capital of the world, set the trend. Where Paris led, the rest of the world eagerly followed.

Ostrich feathers graced everything from elaborate hats to fans, boas, and even entire jackets.

The demand for ostrich feathers extended beyond clothing. They were used in home decor, theatrical costumes, and even as natural dusters due to their unique ability to generate static electricity and attract dust.

Feather Industry History

The ostrich feather industry’s history is marked by dramatic ups and downs. Its roots can be traced back to ancient Egypt, where ostrich plumes were symbols of truth and justice. However, it was during the colonial era that the trade truly flourished.

South Africa’s monopoly on the ostrich feather market seemed unshakeable at first. The country’s farmers even attempted to secure their dominance by acquiring the legendary Barbary ostrich from North Africa, known for its superior feathers.

However, the industry’s success contained the seeds of its own downfall. Overproduction, changing fashion trends, and the outbreak of World War I led to a spectacular market crash. By 1914, the ostrich feather bubble had burst, leaving many farmers ruined.

The Rise and Demise in South Africa

The ostrich feather industry in South Africa experienced a dramatic boom and bust cycle, transforming the Little Karoo region and leaving a lasting economic and cultural impact. This period saw the rise of Oudtshoorn as the ostrich capital, the emergence of wealthy feather barons, and the eventual collapse of the market.

Oudtshoorn Ostriches and the Feather Barons

Oudtshoorn, a town in the Western Cape province, became the epicenter of the ostrich feather trade. The region’s semi-arid climate proved ideal for ostrich farming. As demand for feathers soared, farmers in the Oudtshoorn district pioneered ostrich domestication in the 1850s.

Wealthy landowners, known as feather barons, emerged during this period. They built opulent “ostrich palaces” – grand sandstone mansions that still stand today as testament to the industry’s prosperity. These feather barons wielded significant economic and political influence in the region.

The town’s fortunes were closely tied to the global feather market. At its peak, ostrich feathers were South Africa’s fourth-largest export, trailing only gold, diamonds, and wool.

Colonial Ostrich Farming

Colonial ostrich farming transformed the landscape and economy of the Little Karoo. Farmers developed innovative techniques for breeding, feeding, and plucking ostriches. They introduced lucerne (alfalfa) as a staple feed, which thrived in the region’s climate.

The industry’s growth was rapid. By 1865, feather exports reached 8,600 kg, valued at 125,000 rand – a significant sum at the time. Farmers expanded their operations, fencing large areas for ostrich enclosures.

Colonial authorities supported the industry’s development, recognizing its economic potential. They implemented policies to protect South Africa’s ostrich monopoly, including export restrictions on live birds and eggs.

South African Trade Wars and Economic Shifts

As the ostrich feather trade boomed, South Africa faced challenges from competitors seeking to break its monopoly. The country fought to maintain control over the lucrative North African ostrich populations, also known as red-necked or Barbary ostriches.

International rivals attempted to establish their own ostrich farms, leading to trade tensions. South Africa responded by tightening export controls and investing in breeding programs to improve feather quality.

The industry’s success had far-reaching economic impacts. It attracted immigrants, spurred infrastructure development, and contributed significantly to colonial coffers. However, this prosperity was built on a fragile foundation, dependent on fickle fashion trends.

Feather Market Crash and Colonial Economic Impacts

The ostrich feather market crashed dramatically in 1914.

Feather prices plummeted, leaving many farmers and merchants bankrupt. The crash had a devastating impact on Oudtshoorn and the surrounding region. Many of the grand “ostrich palaces” were abandoned or sold off at a fraction of their value.

The colonial economy, which had become overly reliant on the feather trade, suffered a severe shock. It forced a painful period of economic diversification and restructuring in the Little Karoo.

Little Karoo History

The ostrich feather boom and bust left an indelible mark on the Little Karoo’s history. It shaped the region’s architecture, culture, and economy in ways that are still visible today.

Despite the industry’s collapse, ostrich farming persisted on a smaller scale. Farmers adapted by focusing on ostrich leather and meat production.

Today, Oudtshoorn remains known as the “ostrich capital of the world.” Ostrich farms and related tourism play a significant role in the local economy.

The period also left a rich cultural legacy. Annual festivals celebrate the region’s ostrich heritage, and museums preserve artifacts from the feather boom era. The story of the ostrich feather trade remains a fascinating chapter in South Africa’s colonial and economic history.