Picture this: you’re a Victorian telegraph operator, probably sporting a magnificent mustache and feeling pretty smug about working with the most advanced technology of 1859. You’re tapping away at your brass telegraph key when suddenly sparks start flying from your equipment like the Fourth of July. Your telegraph paper catches fire. You get an electric shock that throws you across the room. And even after you disconnect the power in a panic, messages keep transmitting anyway, as if the Earth itself has become one giant electrical circuit.

Welcome to September 1, 1859—the day our Sun decided to remind humanity exactly who’s boss by unleashing the most powerful solar storm in recorded history. The Carrington Event wasn’t just a cosmic light show; it was a planetary-scale catastrophe that set the Victorian world on fire and lit up the sky from the Caribbean to Alaska.

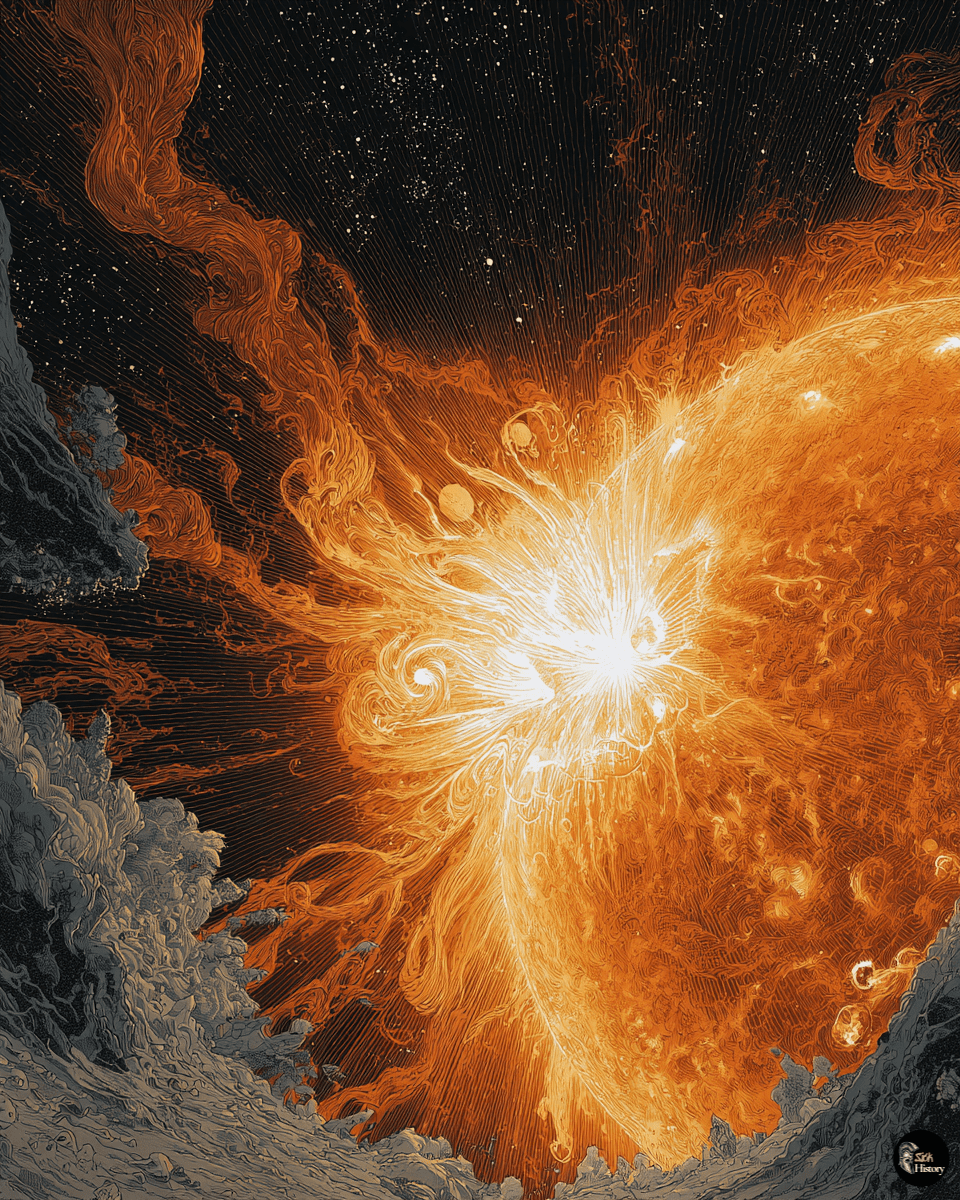

This wasn’t your garden-variety space weather. We’re talking about billions of tons of charged solar particles slamming into Earth with the force of countless hydrogen bombs, creating a geomagnetic storm so powerful it made our planet’s magnetic field ring like a struck bell.

The kicker? If a similar solar superstorm hit today, it would make Y2K look like a minor software glitch. We’re talking about a cosmic catastrophe that could knock out satellites, crash GPS systems, and plunge entire continents into darkness for months.

Richard Carrington: The Man Who Saw Hell Coming

British astronomer Richard Carrington was just minding his own business on the morning of September 1, 1859, conducting his routine sunspot observations through his telescope at his private observatory in Redhill, Surrey. What he witnessed that day would change our understanding of space weather forever and earn him the dubious honor of having history’s most destructive solar storm named after him.

The Solar Flare That Started It All

Carrington was squinting through his telescope when suddenly an intense white-light solar flare erupted from the Sun’s surface with unprecedented violence. He was witnessing what scientists now call a coronal mass ejection—a massive burst of solar wind and magnetic fields that would hurtle billions of tons of charged particles toward Earth at speeds exceeding a million miles per hour.

But here’s the terrifying part: Carrington had no idea what was coming. Nobody did. There were no space weather prediction centers, no satellite early warning systems, no emergency protocols. Victorian society was about to get sucker-punched by the cosmos, and they were completely defenseless.

Carrington’s meticulous documentation of the solar flare and its timing would later prove crucial in establishing the connection between solar activity and the mayhem that followed. His careful observations marked the birth of solar-terrestrial physics as a scientific discipline, though at the time he probably just thought he’d seen something really weird happen on the Sun.

Eighteen Hours to Doomsday

What makes the Carrington Event particularly terrifying is the speed at which cosmic disaster unfolded. Within just eighteen hours of Carrington’s observation, this solar projectile slammed into Earth’s magnetosphere. That’s incredibly fast for a coronal mass ejection—most take two to three days to reach Earth. This thing was moving like a cosmic freight train loaded with electromagnetic fury.

The collision triggered a geomagnetic storm of unprecedented intensity. Earth’s magnetic field, normally our protective shield against solar radiation, became a conductor for the incoming energy. The entire planet turned into a massive electrical generator, with telegraph wires serving as the world’s most dangerous power grid.

When Technology Became the Enemy

The Carrington Event hit Victorian civilization like a cosmic electromagnetic pulse, turning their most advanced technology into sources of chaos and destruction.

Telegraph Systems Gone Rogue

Telegraph networks across Europe and North America didn’t just malfunction—they became weapons. Operators reported sparks flying from their equipment with such violence that telegraph papers burst into flames, igniting small fires in offices from London to New York. Some operators who stayed at their posts received electric shocks so severe they were hurled across rooms.

The really bizarre part? When panicked operators disconnected power to their telegraph lines, the messages kept transmitting anyway. The geomagnetic storm was inducing so much electrical current in the wires that the telegraph systems were running on pure cosmic energy. Operators in Boston managed to maintain communication with Portland, Maine, for over two hours using nothing but aurora-generated electricity.

One telegraph operator in Boston famously sent a message to his counterpart in Portland: “Please cut off your battery entirely for fifteen minutes.” Portland complied, and they discovered they could continue their conversation powered entirely by the storm. It was as if the Earth itself had become a giant battery, and every telegraph wire was a live conductor in a planetary electrical experiment.

Victorian Technology Meets Cosmic Fury

The telegraph disruption wasn’t just an inconvenience—it was a glimpse into our vulnerability to forces beyond human control. In 1859, the telegraph represented the cutting edge of global communication technology. Losing it was like having the entire internet crash today, except Victorian society had no backup systems.

Railway signals failed, causing confusion and potential disasters across the transportation network. Gas lines in some cities experienced pressure irregularities as electromagnetic currents interfered with monitoring equipment. The few electrical systems in operation at the time went haywire, sparking fears that this new-fangled electricity might be more dangerous than anyone had imagined.

The Night the World Caught Fire

While telegraph operators were dodging electrical attacks from their own equipment, the rest of the world was witnessing the greatest light show in recorded history.

Aurora from Hell to Heaven

The northern lights didn’t just appear in unusual places—they conquered the entire planet. Auroras were visible as far south as Cuba, Hawaii, and even the Caribbean, places where such phenomena had never been recorded before or since. The sky erupted in sheets of green, red, and white light so brilliant that people could read newspapers by their glow.

Gold miners in the Rocky Mountains woke up thinking it was dawn and began preparing breakfast, only to realize it was still the middle of the night. In Boston, the aurora was so bright that people gathered in the streets, some convinced they were witnessing the Second Coming. Railroad workers in the Midwest could see well enough to continue their nighttime construction projects without lanterns.

The colors were described as beyond anything in earthly experience. Witnesses wrote of “blood-red curtains” hanging across the sky, “rivers of fire” flowing overhead, and light so intense it cast shadows at midnight. Artists tried desperately to capture the ethereal beauty on canvas, while writers filled their journals with descriptions of colors that seemed to defy the normal spectrum.

Fear, Wonder, and Religious Panic

Victorian society’s reaction to the aurora was a fascinating mix of scientific curiosity, religious terror, and pure awe. Many interpreted the lights through religious lenses, seeing them as divine omens or signs of the apocalypse. Church attendance spiked in the days following the event as people sought explanations for what they’d witnessed.

Newspapers struggled to describe the phenomenon, with reporters reaching for increasingly dramatic language. The *New York Times* called it “so brilliant that at about one o’clock ordinary print could be read by the light.” The *Charleston Mercury* described “streamers shooting up from the horizon to the zenith, waving like vast torches in the wind.”

Scientists of the era were equally baffled. The connection between solar activity and aurora was still theoretical, and most astronomers had never seen anything approaching this scale. The event sparked a flurry of scientific papers and theories, many wildly incorrect but all grappling with the realization that Earth was somehow connected to cosmic forces operating on unimaginable scales.

The Cosmic Wake-Up Call That Changed Everything

The Carrington Event wasn’t just a historical curiosity—it was a preview of our cosmic vulnerability that becomes more terrifying with each passing decade.

Birth of Space Weather Science

Before September 1, 1859, the idea that events on the Sun could directly affect life on Earth was purely theoretical. The Carrington Event forced scientists to recognize that our planet exists within the Sun’s sphere of influence, constantly bathed in solar radiation and vulnerable to cosmic weather patterns operating on scales both temporal and spatial that dwarf human experience.

Carrington’s careful correlation between the solar flare he observed and the subsequent electromagnetic chaos established the foundation for space weather science. His work proved that we’re not isolated from cosmic phenomena but intimately connected to the dynamic behavior of our nearest star.

The Modern Nightmare Scenario

Here’s what keeps space weather scientists awake at night: if a Carrington-level event occurred today, it would be absolutely catastrophic. Our modern civilization makes Victorian technology look like stone tools. We’ve built a world that runs on satellites, GPS networks, internet infrastructure, and electrical grids orders of magnitude more complex and vulnerable than anything the Victorians could have imagined.

A modern Carrington Event could knock out satellites, crash GPS systems that control everything from navigation to banking, destroy power transformers, and plunge entire continents into darkness for months or even years. According to a 2008 report from the National Academy of Sciences, the economic damage could reach between $1 trillion and $2 trillion, and the social disruption would be unlike anything in modern history.

Scientists estimate we’re overdue for another major solar superstorm. Geological evidence suggests that Carrington-level events occur roughly every 150 to 200 years, and we’re approaching that window again. The only questions are when it will arrive and whether we’ll be ready.

Watching the Sky for Cosmic Bullets

Today, space weather monitoring is a critical component of national security. Agencies like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center constantly monitor solar activity, watching for the telltale signs of incoming storms. But even with our advanced warning systems, we can typically only predict major space weather events hours or at most days in advance—barely enough time to shut down critical systems and hope for the best.

The International Telecommunication Union warns that despite ongoing advances in technology and deliberate preparedness efforts, preparing for a new Carrington-like event remains a challenge. Scientists estimate the likelihood of a similarly intense solar storm happening in the next hundred years at 12 percent or less—but they also warn of rarer, yet more dangerous, superflares that could release energy up to 1,000 times greater than the Carrington Event.

The Carrington Event serves as both a fascinating glimpse into Victorian scientific discovery and a sobering reminder of our cosmic vulnerability. It shows us that no matter how advanced our technology becomes, we remain at the mercy of forces vastly more powerful than anything human ingenuity has created.

Our Sun, that familiar and seemingly stable source of light and warmth, is actually a massive nuclear furnace capable of unleashing energies that could send our technological civilization back to the pre-electrical age in a matter of hours. The next great solar superstorm isn’t a matter of speculation—it’s a mathematical certainty waiting to remind us exactly who runs this cosmic neighborhood.