Imagine: you’re living in a cozy mining town in Pennsylvania, going about your daily life, when one day the ground beneath your feet starts literally burning. Not metaphorically burning with passion or excitement—actually on fire, belching toxic smoke, and threatening to swallow your house whole. Welcome to Centralia, Pennsylvania, where what started as a routine trash burning in 1962 became an unstoppable underground inferno that’s still raging today.

This isn’t some ancient geological phenomenon or natural disaster. This is a man-made apocalypse that transformed a thriving community of over 1,000 people into America’s closest approximation of hell on earth. For more than six decades, an underground coal fire has been consuming Centralia from within, forcing the evacuation of nearly every resident and turning the town into a real-life ghost story.

The Centralia mine fire isn’t just burning—it’s thriving. Fed by vast seams of anthracite coal, this subterranean monster reaches temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit and shows no signs of stopping. Scientists estimate it could burn for another century or more, making it one of the longest-running environmental disasters in American history.

Today, smoke vents dot the barren landscape like portals to the underworld, the ground is too hot to walk on in places, and toxic gases seep from cracks in the earth. Of the town’s original population, only a handful of holdouts remain, stubbornly clinging to their homes in what can only be described as a real-life purgatory.

How to Accidentally Create Hell on Earth in One Easy Step

The road to Centralia’s doom was paved with the best of intentions and the worst possible execution. In May 1962, town officials faced a common problem: an overflowing landfill that had become an eyesore and health hazard. Their solution seemed perfectly reasonable for the time—burn the trash.

The Fire That Wouldn’t Die

The controlled burn began on May 27, 1962, and initially everything went according to plan. Volunteer firefighters were on hand to ensure the flames stayed contained. The trash burned, the landfill was cleaned up, and everyone went home thinking they’d solved a problem.

What they didn’t realize was that the fire had found an exposed coal seam. Anthracite coal, the kind that built Pennsylvania’s mining industry, is remarkably efficient at burning—and remarkably difficult to extinguish once it gets going. The flames that were supposed to die out after consuming the trash instead found an essentially unlimited fuel source beneath the ground.

Within days, it became clear that something had gone terribly wrong. Smoke began rising from areas far from the original burn site. The fire had spread underground through the network of abandoned coal mines that honeycombed the area like a vast subterranean city. Efforts to contain the blaze proved futile—you can’t exactly call the fire department to spray water on an underground coal seam.

The Slow-Motion Apocalypse Begins

At first, the underground fire seemed like more of a curiosity than a catastrophe. Sure, there was some smoke here and there, and the ground felt warm in certain spots, but life in Centralia continued much as it always had. Mining families had dealt with industrial hazards for generations—a little underground fire didn’t seem like the end of the world.

But this fire was different. Coal fires burn slowly but persistently, and they’re nearly impossible to extinguish without massive intervention. As the 1960s turned into the 1970s, the fire continued to spread, following coal seams in unpredictable directions. The town that had thrived on coal mining was now being consumed by the very substance that had given it life.

The first signs of serious trouble appeared in the late 1970s. Residents began noticing that their basement walls were uncomfortably warm to the touch. Vegetation started dying in strange patterns across town. Most ominously, the ground began to feel unstable in certain areas, as if the earth itself was being hollowed out from below.

When Your Hometown Becomes a Death Trap

By the early 1980s, living in Centralia had become genuinely dangerous. The underground fire wasn’t just an inconvenience anymore—it was a threat to human life.

The Carbon Monoxide Nightmare

Carbon monoxide detectors, still relatively new technology in the early 1980s, became the soundtrack of Centralia’s slow death. The invisible, odorless gas produced by the underground fire began seeping into homes through basements, foundations, and any crack in the ground. Families reported their CO detectors going off constantly, sometimes multiple times per day.

The scariest part wasn’t just the gas itself—it was the unpredictability. Carbon monoxide pockets could accumulate anywhere, turning a basement into a death trap without warning. Parents feared letting their children play outside, not knowing if the ground beneath a playground might suddenly start venting toxic fumes.

One incident in 1981 crystallized the town’s terror: a massive sinkhole suddenly opened in resident Todd Domboski’s backyard, measuring 4 feet wide and 150 feet deep. The hole revealed the hellscape below—glowing embers and toxic fumes rising from the depths like something out of Dante’s Inferno. Todd himself nearly fell into the pit, saved only by quick thinking and quicker reflexes.

The Great Exodus

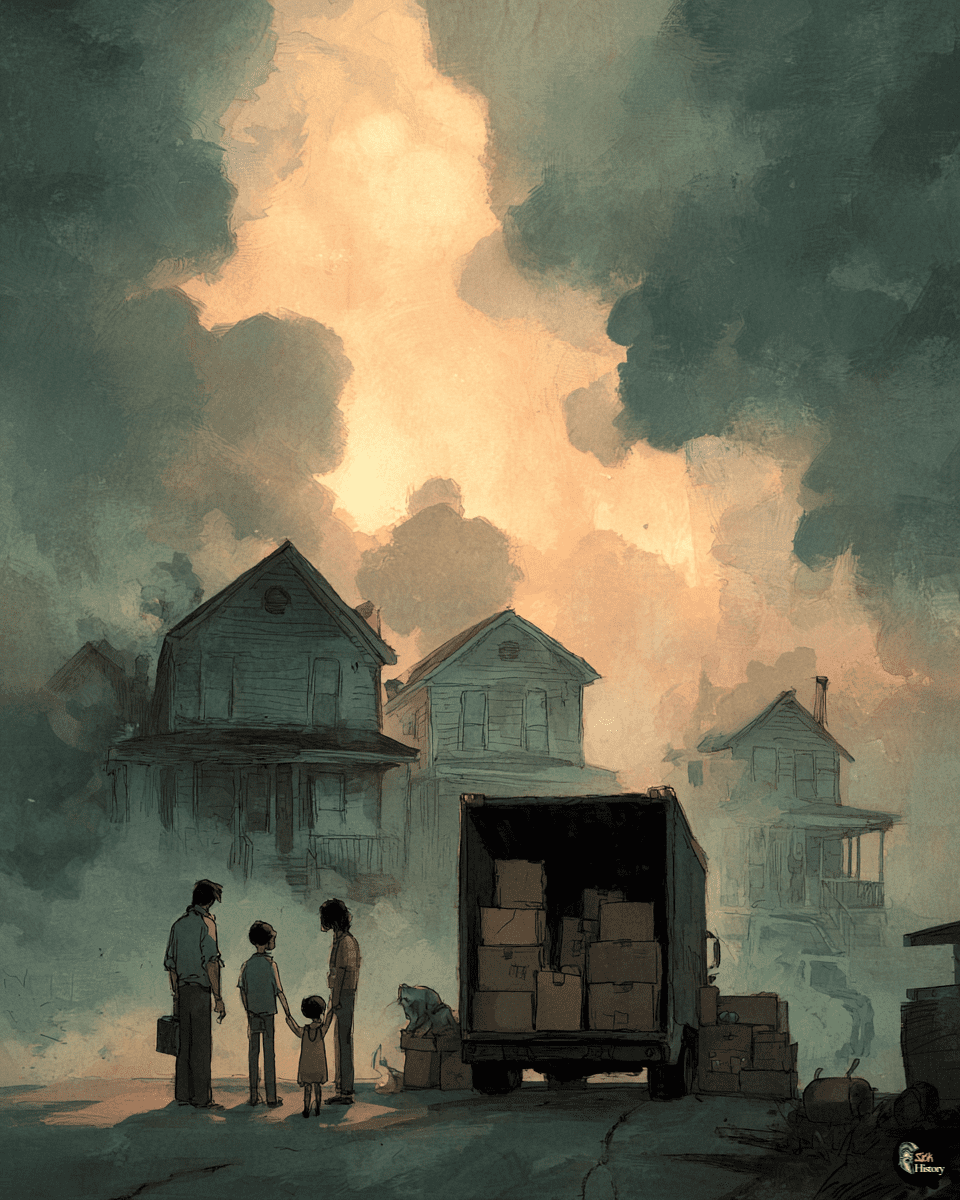

Faced with mounting evidence that their town was uninhabitable, most Centralia residents reluctantly accepted reality. In 1984, Congress allocated $42 million for resident relocation—essentially paying people to abandon their homes and start over elsewhere.

The buyouts created a surreal atmosphere of controlled abandonment. Families packed up decades of memories and walked away from houses their grandparents had built. Children said goodbye to schools, playgrounds, and the only home they’d ever known. Entire neighborhoods gradually emptied, leaving behind a landscape of vacant lots and crumbling foundations.

By the 1990s, Centralia’s population had dwindled from over 1,000 to fewer than 20 residents. The town lost its zip code in 2002, officially ceasing to exist in the eyes of the U.S. Postal Service. Most buildings were demolished to prevent them from becoming hazards, leaving behind a moonscape of empty lots punctuated by the occasional house belonging to holdouts who refused to leave.

The Highway to Hell (Literally)

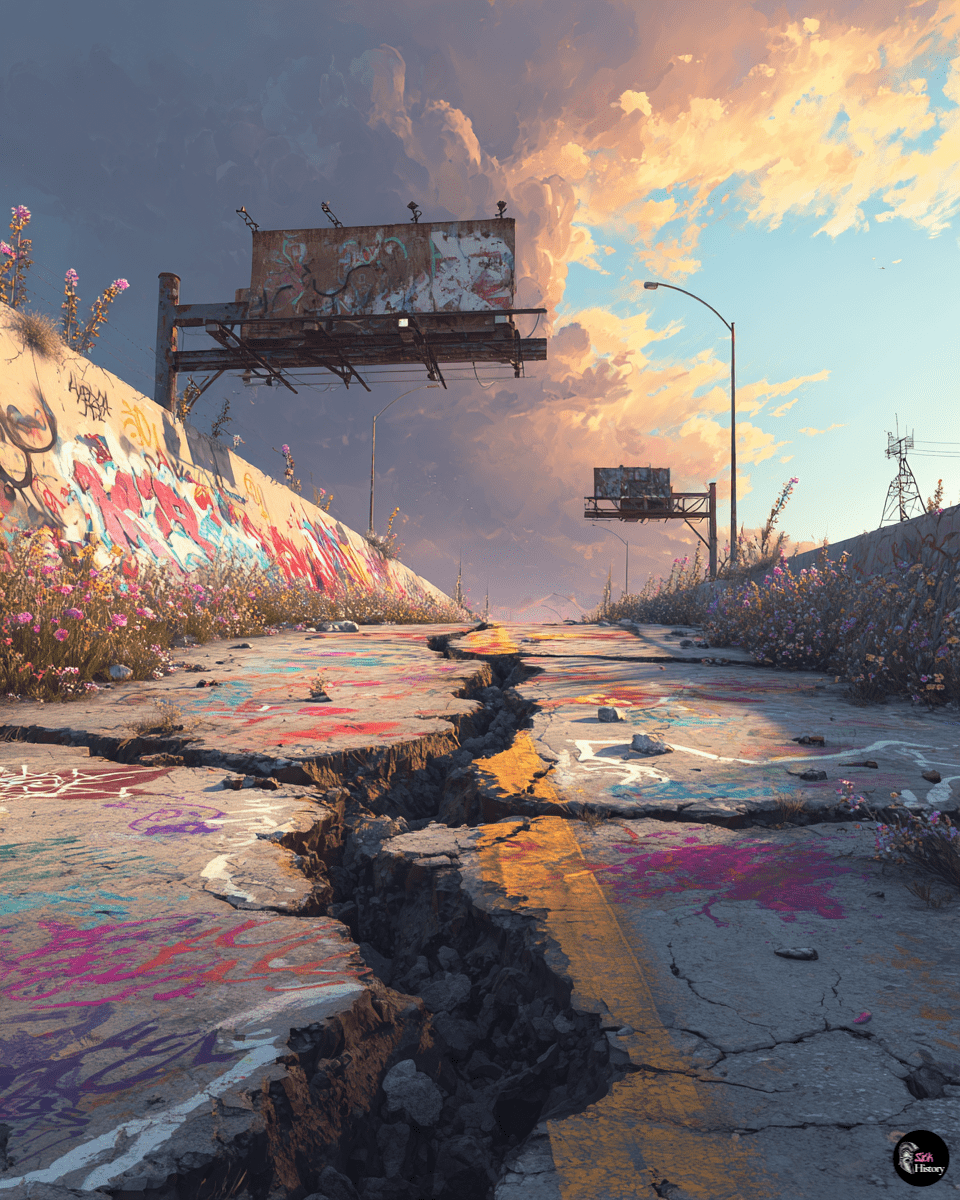

Perhaps no single image captured Centralia’s apocalyptic transformation better than what happened to Route 61, the main highway that once brought commerce and connection to the town.

When Roads Become Casualties

By the early 1990s, the underground fire’s intense heat had begun to destabilize Route 61. Large cracks appeared in the asphalt, some wide enough for a person to fall through. Steam and toxic gases began venting directly through the road surface, creating hazardous driving conditions that grew worse by the month.

The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation faced an impossible situation. Repairing the road was pointless—the underground fire would just crack it again. The heat below was so intense that new asphalt would literally melt. In 1993, officials made the unprecedented decision to permanently close and abandon a section of a major state highway.

The abandoned stretch of Route 61 quickly gained notoriety as the “Graffiti Highway.” Visitors from around the world came to spray-paint messages, artwork, and their names on the broken asphalt. The colorful graffiti created a stark contrast with the apocalyptic landscape, turning the road into an unintentional art installation that attracted urban explorers and dark tourism enthusiasts for decades.

The party ended in 2020 when authorities covered the Graffiti Highway with dirt to discourage trespassers, but by then it had become an iconic symbol of Centralia’s transformation from a place people lived to a place people visited to witness environmental destruction.

The Holdouts: Refusing to Leave Hell

While most Centralia residents accepted buyouts and relocated, a small group of holdouts decided to stay in their burning town, creating one of the strangest residential situations in America.

Life Among the Smoke Vents

Today, fewer than ten residents remain in Centralia, scattered across a landscape that looks more like a post-apocalyptic movie set than a Pennsylvania town. These holdouts live with daily reminders of the fire burning beneath their feet: smoke vents that appear overnight in their yards, ground temperatures hot enough to melt shoe soles, and the constant awareness that their basement could fill with deadly gases without warning.

The remaining residents have developed an almost supernatural ability to coexist with their underground nemesis. They know which areas to avoid, how to read the warning signs of new venting, and how to maintain their homes despite the hostile environment. Some describe their situation with dark humor, joking about living in “the hottest town in Pennsylvania” or having “the world’s most efficient heating system.”

But beneath the gallows humor lies a stubborn determination not to be driven from homes their families have occupied for generations. These holdouts represent the last link between Centralia’s past as a thriving community and its present as an environmental cautionary tale.

The Environmental Horror That Won’t End

More than six decades after it began, the Centralia mine fire continues to burn with no end in sight, creating an ongoing environmental disaster that serves as a stark reminder of industrial hubris.

Toxic Cocktail Rising from the Earth

The underground fire produces a deadly mixture of gases that make large areas of Centralia uninhabitable. Carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane, sulfur dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide continuously vent from cracks in the ground, creating invisible death traps for anyone unaware of the danger.

These toxic gas emissions can accumulate in low-lying areas, basements, or any enclosed space, potentially reaching lethal concentrations. The gases are particularly dangerous because many are odorless and colorless, giving no warning before they strike. Visitors to Centralia have reported sudden headaches, dizziness, and breathing difficulties—symptoms that can quickly progress to unconsciousness or death in areas of high concentration.

The environmental impact extends far beyond the immediate vicinity. Groundwater contamination affects surrounding communities, and air quality suffers throughout the region. The fire has essentially created a permanent pollution source that will continue affecting the environment for generations to come.

The Fire That Could Burn for Centuries

Current estimates suggest the Centralia fire spans approximately 400 acres underground and reaches depths of up to 300 feet. The fire feeds on coal seams that contain enough fuel to sustain combustion for another 250 years or more, making it potentially the longest-burning fire in American history.

Efforts to extinguish the fire have been largely abandoned due to the astronomical costs and technical challenges involved. Early attempts included pumping water and drilling injection holes to introduce fire suppressants, but these proved futile against the vast underground coal reserves. The most comprehensive extinguishment plan, proposed in the 1990s, carried an estimated cost of $663 million—money that lawmakers decided was better spent on other priorities.

America’s Abandoned Mining Legacy

Centralia’s fate reflects a broader pattern of environmental and economic devastation affecting mining communities across America. The town joins a growing list of abandoned mining communities that have fallen victim to industrial accidents, economic collapse, and environmental disasters.

From West Virginia’s Thurmond to California’s Bodie to Colorado’s Gilman, these ghost towns tell similar stories of boom and bust, of communities that thrived on extractive industries only to be abandoned when the resources ran out or the environmental costs became too high. Centralia’s ongoing fire makes it unique, but its fundamental story—a town sacrificed to industrial priorities—echoes throughout America’s mining regions.

The town serves as a powerful reminder that environmental disasters don’t always end when the news cameras leave. Sometimes they burn on for decades, creating permanent scars on the landscape and in the lives of the people who once called these places home.

Centralia continues to burn today, a 62-year-old mistake that transformed a community into a cautionary tale. It stands as proof that some fires, once started, simply refuse to die—and that the consequences of environmental negligence can literally last for centuries. In a world increasingly concerned about climate change and environmental protection, Centralia serves as a stark reminder of what happens when we lose control of the forces we unleash.