Caligula, born Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, ascended to the Roman throne in 37 AD, ushering in a reign that would become synonymous with excess and tyranny.

Initially welcomed by the Roman people, Caligula’s rule quickly descended into a spiral of megalomania and cruelty. His purported attempt to make his favorite horse, Incitatus, a consul exemplifies the bizarre excesses of his short but tumultuous reign.

The young emperor’s erratic behavior and increasingly despotic rule strained relations with the Roman Senate and fueled rumors of mental illness. His insistence on being worshipped as a living god further alienated him from Rome’s political elite and traditional power structures.

The Rise of Little Boot

Born in 12 AD, Gaius earned his nickname “Caligula”—meaning “little boot”—from the miniature military sandals he wore as a child among his father’s legions. Germanicus was Rome’s golden boy, a beloved general whose death in 19 AD left the empire mourning.

When Caligula’s great-uncle Tiberius died in 37 AD, Romans celebrated. Here was their chance for a fresh start—a young emperor with heroic bloodlines and none of Tiberius’ paranoid cruelty.

Caligula’s early moves seemed promising. He recalled exiles, abolished certain taxes, and threw spectacular games for the masses. Rome’s treasury, swollen from Tiberius’ penny-pinching, could afford such generosity.

But something went wrong. Whether from illness, power, or simple madness, the beloved heir transformed into a monster.

God Complex and Horse Politics

Within months of his coronation, Caligula declared himself a living deity. He demanded worship and had temples erected in his honor, forcing senators to prostrate themselves before his divine presence.

His relationship with the Senate became a masterclass in psychological torture. Caligula would force aging senators to run alongside his chariot in the blazing sun, or make them stand for hours while he conducted meaningless ceremonies.

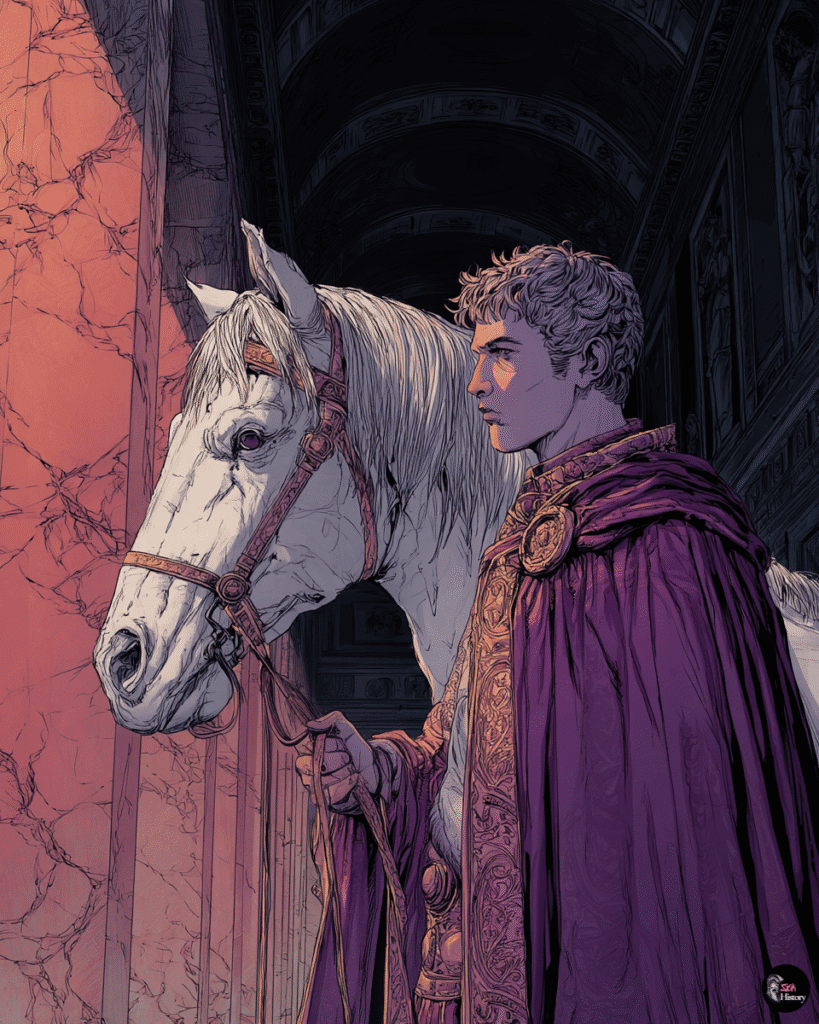

Then came the ultimate insult: his threat to make Incitatus, his prized racehorse, a consul. Whether Caligula was serious or simply taunting Rome’s political elite, the message was clear—his horse deserved more respect than the empire’s most powerful men.

Incitatus lived like royalty, complete with a marble stall and an ivory manger. The horse had servants, fine food, and better accommodations than most Romans. Some sources claim Caligula even planned to build the animal a palace.

The Praetorian Solution

By 41 AD, Caligula’s reign had become unbearable. His extravagant spending had drained the treasury, his paranoia had turned lethal, and his erratic behavior terrorized everyone around him.

The Praetorian Guard—sworn to protect the emperor—had watched their leader descend into madness. When Caligula began threatening their own officers, they reached their breaking point.

On January 24, 41 AD, a group of conspirators found their moment. While Caligula walked alone through a secluded palace corridor, they struck. The assassination was swift and brutal, ending Rome’s most unhinged emperor after just four years of chaos.

His wife and young daughter were also killed in the aftermath, ensuring no revenge from his bloodline.

Legacy of Madness

Caligula’s brief reign left Rome traumatized but wiser. His successor, Claudius, would prove far more stable, but the damage was done. The assassination demonstrated that even emperors weren’t untouchable—a lesson that would echo through Roman history.

Modern historians debate whether Caligula was truly insane or simply drunk on unlimited power. Perhaps the distinction doesn’t matter. What remains is the story of a young man who inherited the world’s greatest empire and nearly destroyed it in four years.

The horse consul threat, whether real or rhetorical, became the perfect symbol of Caligula’s reign—absurd, insulting, and unforgettable. In a city where political dignity meant everything, few acts could have been more devastating to the Roman elite’s pride.

Rome learned that charisma and bloodlines weren’t enough. They needed emperors who understood that ultimate power required ultimate responsibility—a lesson paid for in blood and betrayal.