The year was 1150-something, and the Suffolk village of Woolpit was having what locals probably thought was just another quiet harvest season. Named for the wolf pits that dotted the countryside—deep holes designed to trap the predators that terrorized medieval livestock—Woolpit was the kind of place where the most exciting event might be a traveling merchant or news from the king’s court.

Then two children crawled out of the earth and changed everything.

These weren’t ordinary children who had fallen into the wolf traps. These were beings with green-tinged skin who spoke in an unknown language, refused all food except raw beans, and claimed to come from an underground realm where the sun never shines and everything glows with otherworldly light.

The story of the Green Children of Woolpit stands as one of medieval England’s most baffling mysteries—a tale so strange that it challenges everything we think we know about 12th-century life, yet so well-documented by serious chroniclers that dismissing it as mere folklore becomes surprisingly difficult.

What makes this story particularly unsettling is that it wasn’t recorded by storytellers or folklore collectors, but by respected medieval historians who treated it as fact. When serious chroniclers start documenting impossible events, you’re left with a mystery that has puzzled scholars for nearly 900 years.

The Day Woolpit Met the Impossible

The discovery happened near harvest time, when the fields around Woolpit would have been bustling with activity. Workers were going about their daily tasks when they spotted movement near the wolf pits—those carefully constructed traps that gave the village its name.

Emergence from the Underground

What climbed out of those earthen holes wasn’t a trapped wolf or a lost child, but something that defied the medieval understanding of what was possible. Two children, a brother and sister, emerged from the darkness with skin that possessed an unmistakable green tint. Not the sickly pallor of illness or the dirt-stained complexion of poverty, but an otherworldly green hue that seemed to emanate from within.

The villagers who witnessed this event were struck not just by the children’s appearance, but by their behavior. They spoke in a language no one could recognize—not Latin, not French, not any of the regional dialects that medieval travelers might encounter. It was something else entirely, a tongue that sounded as alien as the children themselves appeared.

Even more disturbing was their reaction to food. Medieval hospitality demanded that hungry children be fed, but these strange visitors rejected every offering. Bread, meat, vegetables, dairy—nothing interested them except raw beans, which they devoured eagerly. It was as if their bodies operated on completely different principles from normal human physiology.

The Green Boy’s Brief Existence

The boy, apparently younger than his sister, never adapted to life in our world. Within a few months of their arrival, he sickened and died, taking with him whatever secrets he might have shared about their origins. His death left only the girl to serve as a bridge between two impossible realities.

But the girl proved remarkably adaptable. Gradually, her green complexion began to fade, shifting toward the normal pale skin tone of medieval English peasants. More importantly, she began to learn the local language, slowly acquiring the ability to communicate with her bewildered hosts.

When she finally possessed enough English to tell her story, what she revealed was more unsettling than her green skin had ever been.

The Testimony of St Martin’s Land

The girl’s account of her origins reads like something from a modern fantasy novel, except it was recorded by 12th-century chroniclers who approached it with the seriousness they would give to any historical event.

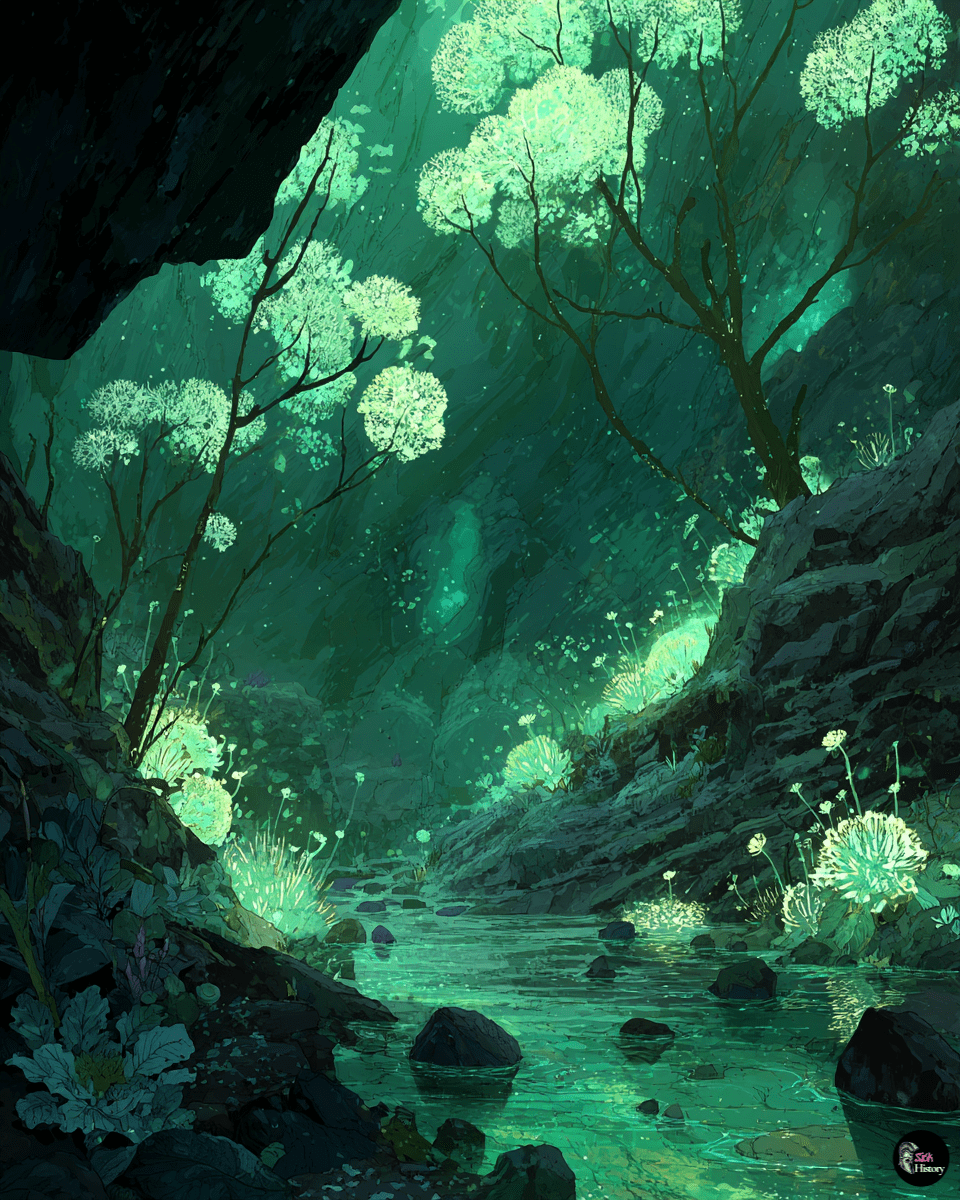

A World Without Sun

According to the girl, she and her brother came from a place called St Martin’s Land—a realm that existed somewhere beneath or alongside our own world. In this place, she explained, the sun never shone. Instead, everything was bathed in a perpetual twilight that somehow provided enough light to sustain life.

The landscape of St Martin’s Land was entirely green, she claimed. Not just the vegetation, but everything—the very air seemed to carry a green tint that colored the entire world. The people who lived there had adapted to this environment, developing the green complexion that had so startled the villagers of Woolpit.

The girl described a pastoral life in this underground realm, where she and her brother had been herding their father’s cattle through green fields under a green sky. It was, by her account, a peaceful existence that might have continued indefinitely if not for the sound that changed everything.

The Sound of Bells

The children’s journey to our world began, according to the girl’s testimony, with the sound of distant bells. In St Martin’s Land, these bells were unusual enough to attract curiosity. Following the sound, the children discovered a cave or passage that seemed to lead toward the source of the mysterious ringing.

What happened next depends on which version of the story you follow, but the essential elements remain consistent: the children found themselves in a tunnel or cave system that led them away from their green world and into ours. When they emerged from the wolf pits near Woolpit, they had crossed not just physical distance but what seemed to be the boundary between two entirely different realities.

The girl never provided a clear explanation for how this journey was possible or why they couldn’t simply return the way they came. Perhaps the passage only worked in one direction, or perhaps the trauma of adapting to our world had somehow severed their connection to St Martin’s Land. Whatever the mechanism, it seemed that their arrival in Woolpit was permanent.

The Chroniclers Who Made It History

What elevates the Green Children of Woolpit from folklore to historical mystery is the quality of the sources who recorded it. This wasn’t a story passed down through oral tradition or recorded by traveling entertainers—it was documented by two of the most respected chroniclers of 12th-century England.

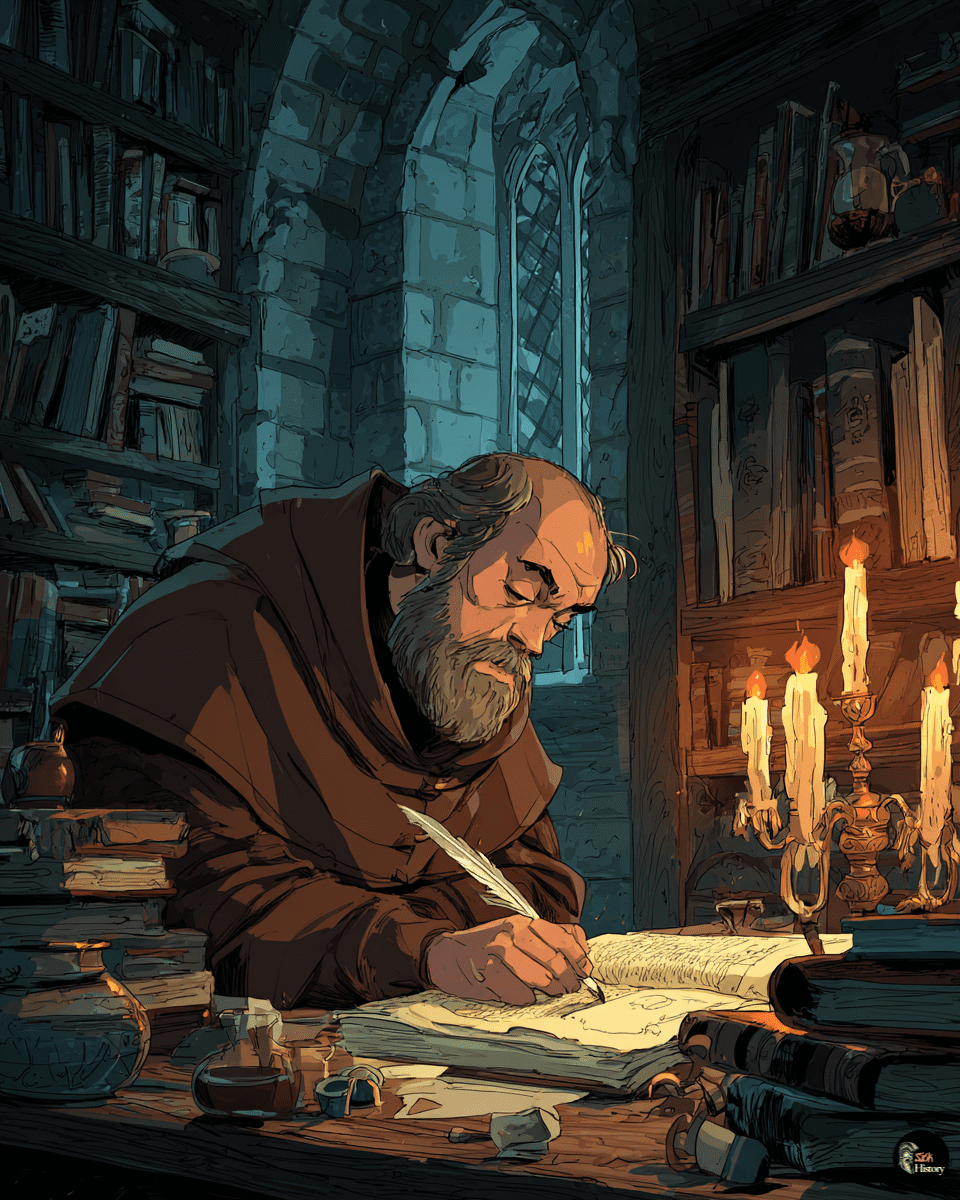

William of Newburgh: The Skeptical Historian

William of Newburgh, writing his “Historia rerum Anglicarum” in the 1190s, included the green children story alongside other historical events of the period. What makes his account particularly compelling is that William was known for his critical approach to sources—he was the same chronicler who famously dismissed Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Arthurian histories as fiction.

Yet William treated the green children story as worthy of inclusion in his serious historical work. He approached it with the same methodical documentation he applied to political events and military campaigns, suggesting that he believed something genuinely unusual had occurred in Woolpit.

William’s account includes details about the children’s behavior, their gradual adaptation to normal food, and the girl’s eventual integration into English society. He presents it not as a wonder tale, but as a documented event that happened to fall outside normal human experience.

Ralph of Coggeshall: The Connected Witness

Even more compelling is the account of Ralph of Coggeshall, who claimed to have heard the story directly from Sir Richard de Calne, the knight who had taken the children into his household. This creates a direct chain of testimony from the children themselves to one of England’s most respected abbots.

Ralph’s version includes additional details about the children’s time in de Calne’s care and the girl’s eventual fate. According to his account, she was baptized, learned to speak fluent English, and eventually married—living what appears to have been a normal life despite her extraordinary origins.

The fact that two independent chroniclers recorded similar versions of the story, and that one claimed direct access to a primary witness, makes the Green Children of Woolpit one of the best-documented “impossible” events in medieval history.

Theories, Explanations, and Enduring Questions

For nearly 900 years, scholars have attempted to explain the Green Children of Woolpit through various rational theories, none of which fully satisfy the documented evidence.

Medical Explanations

The most commonly proposed explanation is chlorosis, a form of anemia that can cause a greenish tint to the skin. This condition, sometimes called “green sickness,” was known to medieval physicians and could potentially explain the children’s unusual coloration.

However, chlorosis typically affects adolescent girls and doesn’t explain the children’s unfamiliar language, their specific dietary restrictions, or their detailed knowledge of an alternative world. It also doesn’t account for how they ended up in the wolf pits or why they seemed so genuinely alien to their medieval observers.

Other medical theories have suggested arsenic poisoning, dietary deficiencies, or rare genetic conditions, but each explanation raises as many questions as it answers.

Cultural and Historical Context

Some historians have suggested that the children might have been Flemish immigrants who became lost and malnourished, developing the green skin tint through poor diet and possibly wearing green clothing that stained their skin. The “unknown language” could have been Flemish, which would have been unfamiliar to Suffolk villagers.

This theory attempts to ground the story in the known historical context of 12th-century England, when political turmoil and foreign settlement were common. However, it still doesn’t explain the children’s detailed descriptions of St Martin’s Land or why experienced chroniclers would present such an explanation as supernatural.

The Folklore Dimension

The story contains elements common to fairy tales and folklore traditions throughout Europe—otherworldly visitors, underground realms, and the crossing between different worlds. Some scholars have suggested that the Green Children represent a literary creation that incorporates these traditional elements.

But this interpretation faces the same problem as the others: it doesn’t account for why serious historians would present a folklore motif as contemporary historical fact, or why the story contains such specific and seemingly credible details about the children’s adaptation to normal life.

The Mystery That Refuses to Die

What makes the Green Children of Woolpit enduringly fascinating isn’t just the strangeness of the original story, but the way it challenges our assumptions about medieval England and the nature of historical evidence.

A Window into Medieval Worldview

The story reveals how 12th-century people understood the boundaries between the natural and supernatural worlds. For medieval chroniclers, the appearance of green children from an underground realm wasn’t necessarily more impossible than many other events they recorded—divine interventions, miraculous healings, and supernatural occurrences were part of their normal historical framework.

This doesn’t mean they were gullible; it means they operated with a different understanding of what was possible. The careful documentation of the green children story suggests that even by medieval standards, this event was considered unusual enough to require detailed recording.

The Problem of Evidence

The Green Children of Woolpit presents a unique problem for historians: how do you handle well-documented accounts of events that seem to defy rational explanation? The story is too well-sourced to dismiss as folklore, too detailed to explain as misunderstanding, and too strange to accept as conventional history.

Perhaps that’s the point. Some mysteries resist explanation not because we lack sufficient information, but because they represent encounters with possibilities that exist outside our normal frameworks of understanding. The green children may have been visitors from another dimension, time travelers, beings from a parallel world, or something else entirely that our current scientific understanding can’t accommodate.

Or perhaps they were simply children with a medical condition and active imaginations, whose story was transformed by the medieval chroniclers who recorded it. The truth may be far more mundane than the legend suggests, lost in the gap between what happened and what was written down.

The Enduring Power of Mystery

Nine centuries after two strange children emerged from the wolf pits of Woolpit, their story continues to captivate imaginations and challenge explanations. It represents something that seems increasingly rare in our modern world: a genuine mystery with no clear solution.

The Green Children of Woolpit remind us that history is full of events that resist easy categorization, stories that exist in the borderlands between fact and fantasy, documentation and imagination. Whether they were visitors from another world, victims of circumstance, or something else entirely, they left behind one of the most compelling unexplained events in medieval English history.

In our age of instant information and scientific explanation, perhaps we need stories like this—tales that remind us that some questions may never be answered, and that the universe may be far stranger than our current understanding allows. The green children of Woolpit, whether real or imagined, continue to serve as ambassadors from the realm of the impossible, challenging us to consider what other mysteries might be waiting in the wolf pits of history.