The 1957 Spaghetti Tree hoax stands as a testament to the power of media and the gullibility of audiences.

On April Fool’s Day, the BBC’s Panorama program aired a seemingly innocuous segment about a Swiss family harvesting spaghetti from trees. The hoax fooled millions of viewers, many of whom called the BBC asking how they could grow their own spaghetti trees.

This elaborate prank tapped into a peculiar convergence of cultural naivety and trust in broadcast media.

At the time, spaghetti was relatively unknown in Britain, and the idea of pasta growing on trees didn’t seem as far-fetched as one might imagine.

The three-minute hoax report was meticulously crafted, featuring a family in southern Switzerland carefully plucking strands of spaghetti from branches.

The success of the Spaghetti Tree hoax reveals much about human psychology and the relationship between media and its audience.

It raises questions about the nature of belief, the role of authority in shaping our perceptions, and the thin line between fact and fiction in the information we consume.

Origins of the Hoax

The Spaghetti Tree hoax emerged from a perfect storm of British unfamiliarity with pasta and the creative minds at the BBC.

It showcased the power of television to shape public perception and the enduring appeal of a well-crafted prank.

Panorama Broadcast

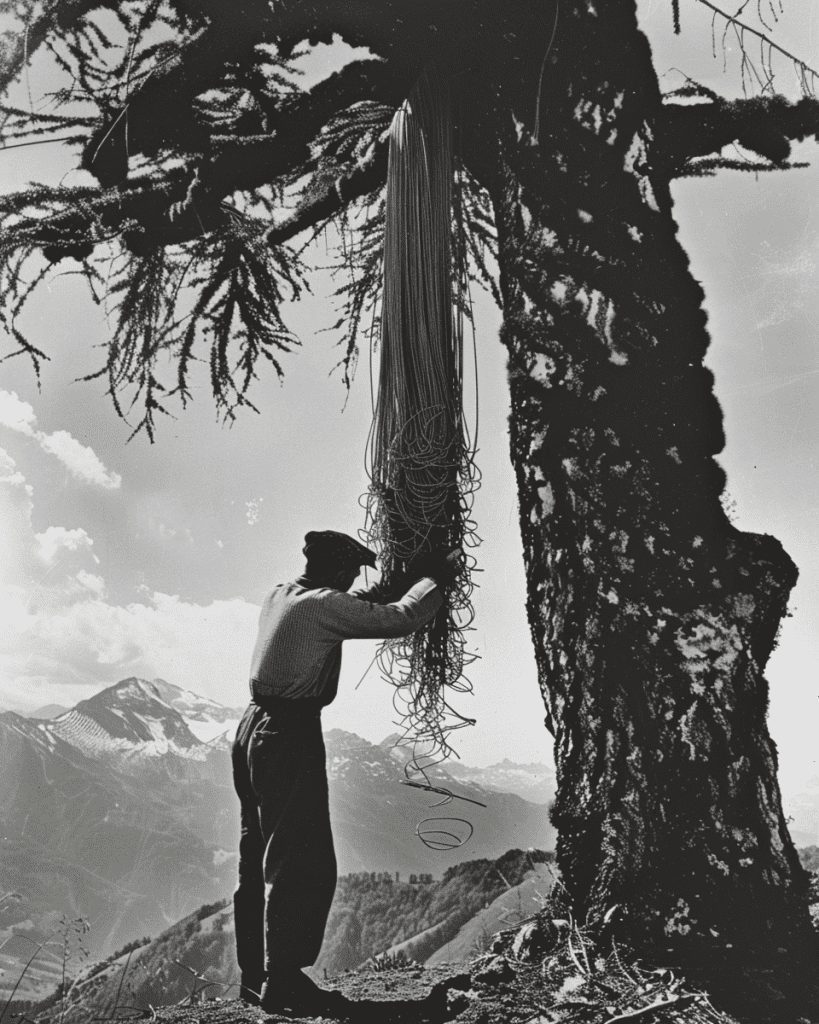

On April 1, 1957, the BBC’s respected current affairs program Panorama aired a three-minute segment about a family in Ticino, Switzerland, harvesting spaghetti from trees.

The piece was meticulously crafted, featuring footage of women carefully plucking strands of spaghetti from branches and laying them in the sun to dry.

Austrian-born cameraman Charles de Jaeger, known for his practical jokes, conceived the idea.

He drew inspiration from his school days when teachers would tease students by asking, “Did you ever see the spaghetti harvest in Switzerland?”

The segment’s success hinged on the British public’s limited knowledge of spaghetti.

Many viewers were unaware that pasta came from wheat, making the concept of spaghetti trees seem plausible.

Richard Dimbleby’s Role

Richard Dimbleby, a respected broadcaster, played a crucial part in lending credibility to the hoax.

His gravitas and reputation for journalistic integrity made the segment all the more convincing.

Dimbleby’s narration described the annual spaghetti harvest with utmost seriousness.

He explained how the mild winter and virtual disappearance of the spaghetti weevil had ensured a bumper crop.

His involvement was a masterstroke.

Viewers accustomed to trusting Dimbleby’s reporting found it difficult to question the veracity of the story. This trust, combined with the segment’s high production values, created a perfect illusion that captivated the nation.

Public Reaction and Believability

The 1957 Spaghetti Tree hoax captivated audiences and sparked widespread curiosity. Its impact reverberated through society, challenging perceptions and highlighting the power of media.

Immediate Public Response

Viewers across Britain were thoroughly convinced by the BBC’s spaghetti tree segment.

Many called the network, eager to learn how they could grow their own pasta-bearing plants. The broadcaster’s reputation for trustworthiness lent credibility to the prank.

Some audience members expressed genuine excitement about this “agricultural breakthrough.” Others questioned their understanding of pasta production, suddenly uncertain about its true origins.

The hoax exposed a knowledge gap about spaghetti among the British public.

At the time, pasta was still considered an exotic food in the UK, contributing to the prank’s effectiveness.

Media Coverage

News outlets buzzed with discussions of the Spaghetti Tree hoax.

Initial reports focused on repeating the BBC’s claims, inadvertently spreading the misinformation further.

As the truth emerged, media attention shifted to analyzing the prank’s success.

Journalists explored why so many had been fooled, sparking debates about media literacy and critical thinking.

The incident became a cautionary tale in journalism schools.

It highlighted the need for fact-checking and skepticism, even when dealing with reputable sources.

Influence on Popular Culture

The Spaghetti Tree hoax left an indelible mark on popular culture.

It became a touchstone for discussions about media pranks and gullibility.

References to spaghetti trees appeared in comedy sketches and sitcoms for years afterward. The phrase “spaghetti harvest” entered the lexicon as a shorthand for absurd claims.

The hoax inspired future April Fools’ Day pranks in the media and set a high bar for creativity and believability in such stunts.

Even decades later, the Spaghetti Tree hoax remains a cultural reference point.

It’s often cited in discussions about the power of visual media to shape beliefs and perceptions.

Analysis of the Hoax’s Success

The Spaghetti Tree hoax captivated audiences through a perfect storm of credibility, social context, and persuasive elements. Its success hinged on the public’s trust in television and limited knowledge of foreign cuisine.

Credibility of the Source

The BBC’s reputation as a trusted news source played a crucial role in the hoax’s success.

Panorama, known for its serious reporting on current affairs, lent an air of authenticity to the segment. Richard Dimbleby, a respected broadcaster, narrated the story with his characteristic gravitas.

This combination of a reputable network and a well-known presenter fooled many viewers into believing the improbable tale.

The use of seemingly genuine footage, complete with Swiss locals harvesting spaghetti, further enhanced the illusion.

The timing of the broadcast on April Fools’ Day was a masterstroke.

Many viewers were caught off guard, not expecting such a prank from a serious news program.

Social Context of the 1950s

The 1950s provided fertile ground for the Spaghetti Tree hoax to take root.

Post-war Britain was experiencing rapid changes, including exposure to new foods and cultures.

Spaghetti was still a relatively exotic food for many Britons. Its unfamiliarity made the idea of it growing on trees seem plausible to some.

The average person’s limited travel experiences and lack of knowledge of global cuisine contributed to this misconception.

Television was still a new medium, and viewers were less skeptical of its content.

The power of visual media to shape perceptions was not yet fully understood or questioned by the general public.

Elements of Persuasion Used

The hoax employed several persuasive techniques to enhance its credibility:

- Visual evidence: Carefully staged footage of people harvesting spaghetti from trees.

- Scientific-sounding explanations: References to the “spaghetti weevil” and ideal growing conditions.

- Cultural stereotypes: The use of a Swiss setting played into British notions of the exotic.

The segment’s brevity worked in its favor, providing just enough information to seem plausible without inviting too much scrutiny.

The deadpan delivery and matter-of-fact tone lulled viewers into accepting the story at face value.

By blending fact and fiction, the hoax created a narrative that was just believable enough to capture the imagination of its audience. This delicate balance between the familiar and the fantastical was key to its widespread acceptance.

Hoax Exposed

The unraveling of the spaghetti tree hoax revealed both the BBC’s cunning and the public’s gullibility. It demonstrated how easily misinformation could spread, even in an era before the internet.

BBC’s Subsequent Revelation

The BBC waited until the evening of April 1st to disclose the truth behind the spaghetti tree segment.

They announced that the story was, in fact, an elaborate April Fool’s joke. This revelation shocked many viewers who had genuinely believed in the existence of spaghetti trees.

The network’s decision to air such a convincing hoax sparked debates about media responsibility and the power of television.

It highlighted how visual evidence, even when fabricated, could override common sense and basic knowledge.

Public Admittance of Being Fooled

The aftermath of the hoax exposed a surprising level of public naivety.

Hundreds of people contacted the BBC, eager to learn how they could grow their own spaghetti trees. Some even asked where they could purchase spaghetti plant seedlings.

This widespread belief in the hoax reflected a general lack of knowledge about pasta production at the time. It also demonstrated the immense trust viewers placed in television news.

The incident became a cultural touchstone, often cited as an example of media influence and the importance of critical thinking.

It served as a reminder that not everything seen on television should be taken at face value.

Legacy of the Spaghetti Tree

The BBC’s spaghetti tree hoax left an indelible mark on broadcasting and public perception. It sparked discussions about media literacy and reshaped approaches to news reporting.

Educational Implications

The hoax became a powerful teaching tool.

Educators began using it to illustrate the importance of critical thinking and media skepticism. Students learned to question seemingly authoritative sources, even respected institutions like the BBC.

This incident highlighted the public’s limited knowledge of foreign cultures and cuisines in 1950s Britain.

It prompted schools to broaden their curricula, incorporating more diverse cultural studies.

The hoax also served as a cautionary tale about the potential for misinformation.

It demonstrated how easily false information could spread, even in an era before social media and instant communication.

Impact on Broadcasting Standards

The spaghetti tree prank led to significant changes in broadcasting practices.

News organizations became more cautious about airing potentially misleading content, even in jest.

April Fools’ Day broadcasts came under increased scrutiny.

Many networks implemented stricter guidelines for humor and satire in news programming.

The incident sparked debates about the role of public broadcasting.

Should taxpayer-funded entities engage in pranks? This question led to more defined ethical standards in public media.

Paradoxically, the hoax also encouraged more creative storytelling in documentaries.

Filmmakers realized the power of visual narratives to captivate audiences, leading to more engaging educational content.

Comparisons to Modern Misinformation

The Spaghetti Tree hoax of 1957 shares striking parallels with contemporary misinformation, while also highlighting how media literacy has evolved over the decades. Its success and impact offer insights into the nature of deception and public credulity.

Similar Contemporary Hoaxes

In recent years, we’ve seen hoaxes that rival the Spaghetti Tree in their audacity and reach.

The “Dihydrogen Monoxide” scare, which simply rebranded water as a dangerous chemical, fooled many.

Another example is the “Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus” hoax, a fictional endangered species that gained traction online.

These modern myths exploit the same human tendencies as the Spaghetti Tree hoax: a willingness to believe authoritative sources and a lack of specialized knowledge.

The key difference? Today’s hoaxes spread rapidly through social media, reaching millions in hours rather than days.

Evolution of Media Literacy

The Spaghetti Tree hoax occurred in an era of limited media options and high trust in broadcasters.

Today’s media landscape is vastly different.

We’re more skeptical, yet paradoxically more susceptible to misinformation.

The sheer volume of information we encounter daily makes discernment challenging.

Media literacy education has become crucial.

Schools now teach critical thinking skills specifically for navigating digital content.

Fact-checking websites have proliferated, offering quick verifications of dubious claims.

Yet, as our defenses evolve, so do the tactics of those spreading misinformation.

It’s an ongoing arms race between truth and deception.