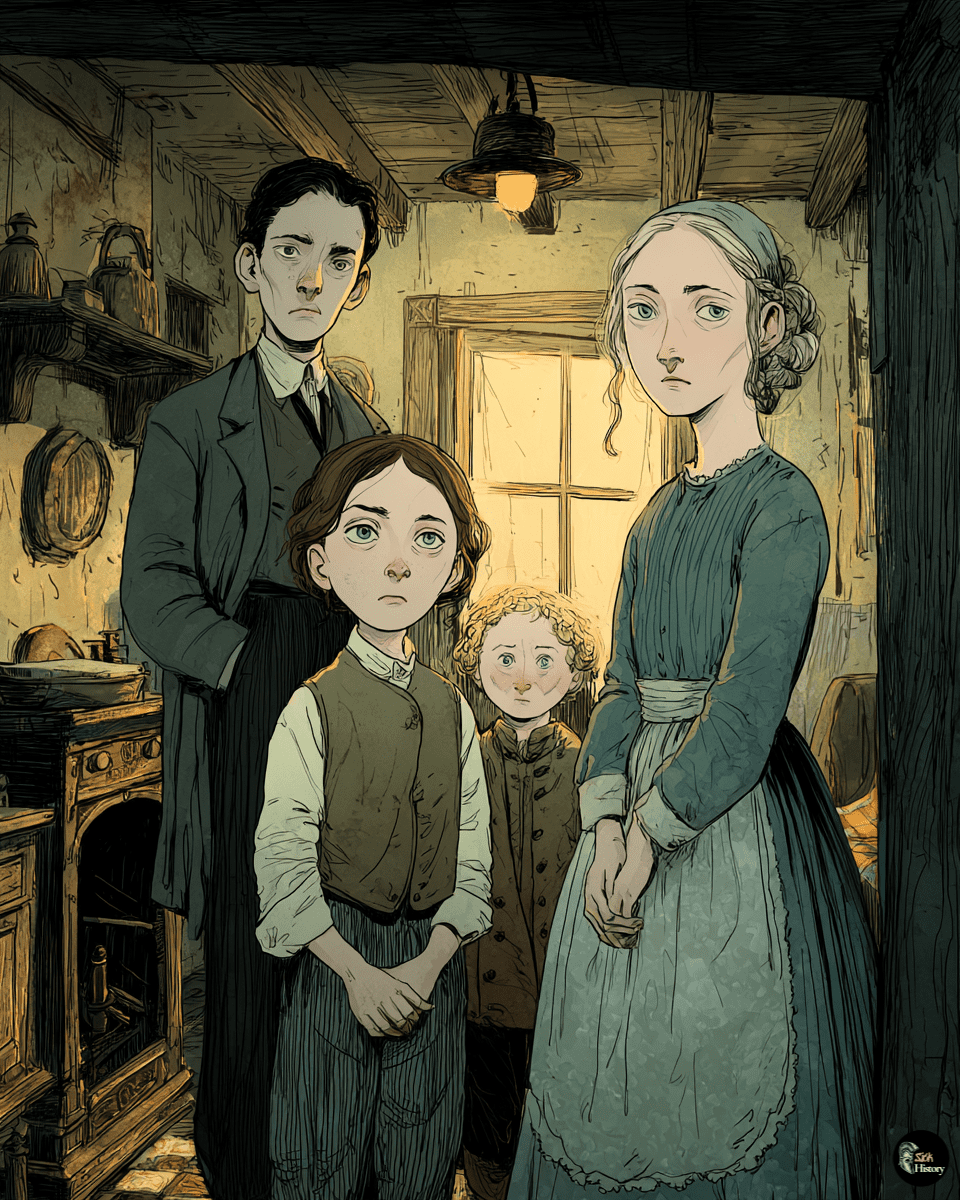

Sarah Fletcher had just finished her weekly shopping at Bradford’s bustling Saturday market when she spotted the peppermint sweets. Her three children had been especially well-behaved that week, and the two ounces of candy seemed like the perfect weekend treat. The vendor, “Humbug Billy” Hardaker, even offered her a discount—the latest batch looked a bit different, he explained, so he was selling them cheaper than usual.

By Sunday evening, all three of Sarah’s children were dead.

They weren’t alone. Across Bradford on that October weekend in 1858, families who had bought the same “harmless” sweets were planning funerals instead of family dinners. What had started as a simple pharmacy mistake became one of Victorian Britain’s deadliest accidental poisonings, killing 20 people and sickening over 200 others with arsenic-laced candy in a disaster that exposed the horrifying reality of unregulated Victorian medicine.

The Bradford sweets poisoning wasn’t an isolated incident—it was the inevitable result of a pharmaceutical system so dangerously unregulated that trusted healers could become mass murderers through simple incompetence. In Victorian Britain, your neighborhood pharmacy was essentially a chemistry set run by people with no training, no oversight, and no understanding of the difference between medicine and poison.

The Arsenal in Every Apothecary

To understand how entire families could be accidentally poisoned by their local pharmacy, you need to appreciate just how casually Victorian society treated substances that would make modern toxicologists break out in cold sweats.

Arsenic: The Everyday Killer

Arsenic in Victorian pharmacies wasn’t an aberration—it was standard inventory. Known as “the king of poisons,” arsenic was paradoxically considered one of the most versatile medicines of the era. Pharmacies stocked it alongside sugar and flour, often in identical containers with minimal labeling.

Victorian doctors prescribed arsenic for an astounding array of conditions: syphilis, malaria, skin diseases, digestive problems, and even as a general tonic for people who just felt a bit under the weather. “Fowler’s Solution,” a popular arsenic-based tonic, was available over the counter and marketed as a health drink. “Paris Green,” an arsenic-based rat poison, was sometimes repurposed as a medical treatment.

The logic seemed sound at the time. Arsenic could kill parasites, reduce inflammation, and appeared to improve certain conditions when used in small doses. What Victorian medicine didn’t understand was the concept of bioaccumulation—the way arsenic builds up in the body over time, creating a delayed-action poison that could kill patients weeks or months after they stopped taking it.

The Wild West of Victorian Pharmacies

The pharmaceutical landscape of 1850s Britain resembled the American frontier more than a regulated medical system. There were no licensing requirements for druggists until the Arsenic Act of 1851, and even then, enforcement was inconsistent. Anyone could hang a shingle and call themselves a pharmacist, often learning their trade through trial and—sometimes fatal—error.

This created a perfect storm of good intentions and dangerous ignorance. Many druggists genuinely wanted to help their customers and took pride in their ability to compound effective medicines. But they were working with incomplete knowledge, dangerous substances, and no safety net to prevent catastrophic mistakes.

The Bradford disaster illustrated this perfectly: a pharmacy assistant who had been on the job for just a few weeks was left alone to handle customer requests, with access to barrels of deadly poison stored alongside harmless substances in identical containers.

The Bradford Massacre: How Candy Became Poison

The chain of errors that led to the Bradford poisoning reads like a textbook example of how unregulated systems can turn deadly.

A Simple Request Goes Horribly Wrong

William Neal, a local confectioner, had run out of “daft”—powdered gypsum used to bulk up candy and reduce costs. He sent his lodger, James Archer, to Charles Hodgson’s pharmacy in nearby Shipley to purchase more of the harmless white powder.

When Archer arrived at the pharmacy, Hodgson was ill in bed. His assistant, William Goddard, had been working there for only a few weeks and was told to find the daft in a barrel in the attic. What Goddard didn’t realize was that there were two identical barrels, and he grabbed 12 pounds of arsenic trioxide instead of gypsum. The arsenic barrel was labeled—but only on the bottom.

This wasn’t malicious negligence; it was the inevitable result of a system with no safety protocols. No double-checking procedures, no training requirements, no standardized storage systems. Just a young man making a guess about which of two identical barrels contained what he needed.

Warning Signs Ignored

Back at Neal’s confectionery, experienced sweet maker James Appleton noticed immediately that something was different about this batch. The mixture was more free-flowing and smoother than usual, and the finished sweets came out darker than normal. Both Appleton and Neal even began feeling sick—Appleton suffered fits of vomiting from working closely with the arsenic.

But neither man connected their illness to the sweets. In an era before understanding of occupational hazards, getting sick while working was considered normal. They had no framework for thinking that their own product might be poisoning them.

When “Humbug Billy” Hardaker came to collect the sweets for his market stall, he too noticed the unusual color. Rather than rejecting the batch, he negotiated a lower price and sold them to unsuspecting families as a weekend treat.

Death Comes to Bradford

The arsenic-laced sweets went on sale Saturday evening at Bradford’s Green Market. Hardaker sold them in two-ounce portions for a penny and a half—a reasonable price for a family treat. He even ate some himself and became ill by evening, but like the confectioners, he didn’t connect his sickness to the product.

A Weekend of Horror

By Sunday morning, Bradford’s police were receiving reports of mysterious deaths throughout the city. The initial diagnosis was cholera—the symptoms were virtually identical, and England was in the midst of an ongoing cholera pandemic. It wasn’t until Police Constable Campbell noticed the pattern and made the connection to the sweets that the true horror became clear.

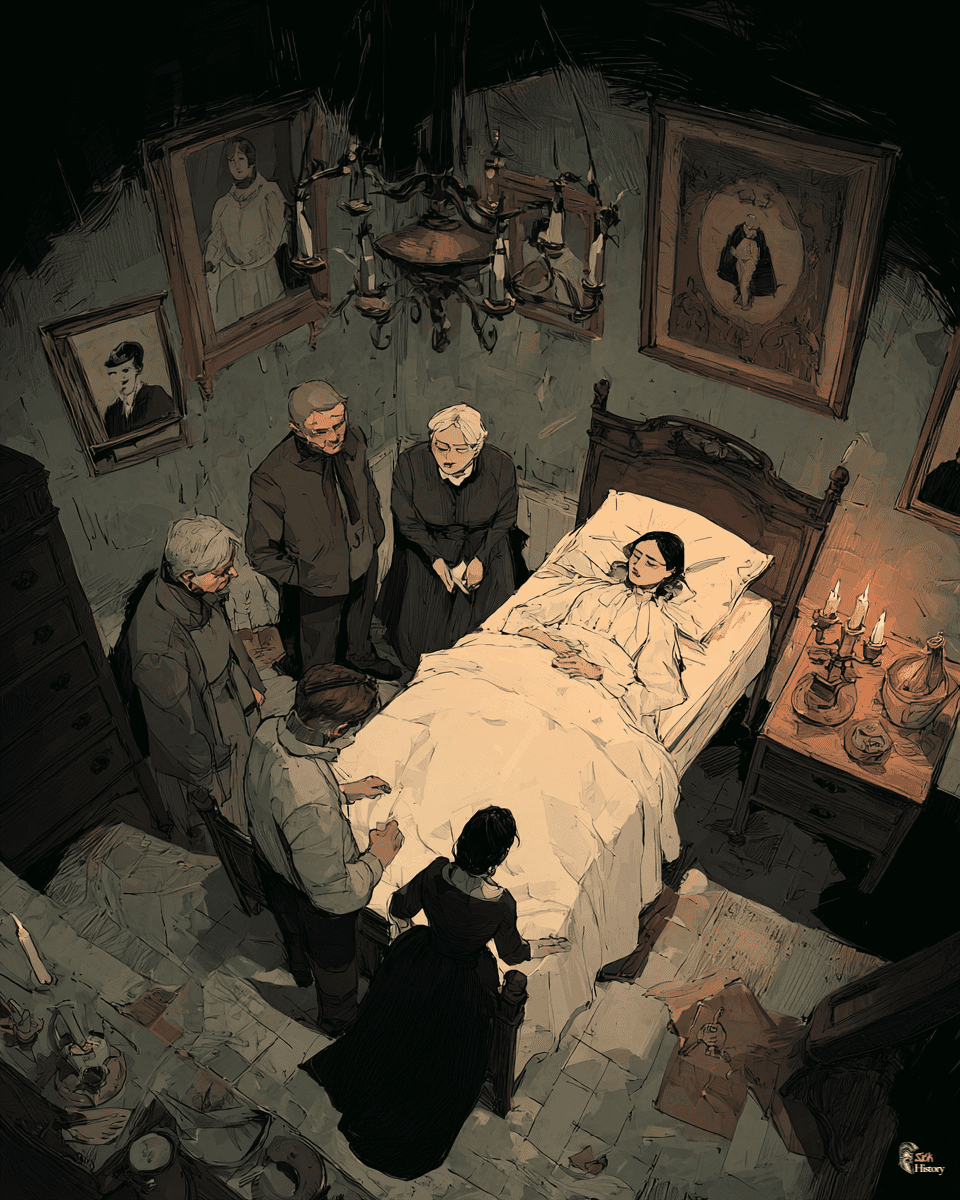

Families who had bought the candy as a weekend treat watched their children convulse with stomach pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. The youngest victims suffered the most—their smaller bodies couldn’t process even small amounts of the poison. Parents who had given the sweets as rewards for good behavior found themselves planning funerals instead of family outings.

The final toll was devastating: 20 dead, including a 9-year-old and a 14-year-old boy, and over 200 people seriously ill. Entire families were wiped out by what should have been a harmless treat.

Justice and Reform in Victorian Britain

The Bradford poisoning sent shockwaves through Victorian society and exposed the deadly consequences of unregulated pharmaceutical practice.

A Trial That Shocked the Nation

Three men were arrested in connection with the deaths: the pharmacist Charles Hodgson, his assistant William Goddard, and sweet maker William Neal. The trial that followed captivated the nation, not least because it raised fundamental questions about accountability in an unregulated system.

The judge ultimately acquitted all three men, ruling that the deaths were entirely accidental and that none of the defendants had criminal intent. This decision, while legally sound, highlighted the moral vacuum at the heart of Victorian pharmaceutical practice: if nobody was responsible for checking the safety of medicines, who could be held accountable when things went wrong?

The Birth of Modern Pharmaceutical Regulation

The Bradford disaster became a catalyst for urgent reform. The deaths led directly to the Adulteration of Food or Drink Act 1860 and were a major factor in the passage of the Pharmacy Act 1868, which established the first comprehensive regulations for pharmaceutical practice in Britain.

These reforms introduced radical concepts that we now take for granted: licensing requirements for pharmacists, standardized training, proper labeling of dangerous substances, and accountability for pharmaceutical safety. The idea that druggists should be held to professional standards rather than operating as unregulated entrepreneurs was revolutionary.

But the reforms came too late for the families of Bradford, and they didn’t immediately solve the broader problem of arsenic in everyday life.

The Arsenic Century: Britain’s Toxic Romance

The Bradford poisoning was just one incident in what historians now call “the arsenic century”—a period when Victorian Britain was systematically poisoning itself through industrial negligence and medical ignorance.

Arsenic Everywhere

Arsenic wasn’t confined to pharmacies—it permeated Victorian life. Wallpaper contained arsenic-based green pigments that could poison entire families through toxic fumes. Clothing dyes used arsenic compounds that could cause skin poisoning. Children’s toys were painted with arsenic-based colors. Even candles and beer contained traces of the poison.

The ubiquity of arsenic created a perfect storm for accidental poisoning. Families could be slowly poisoned by their own homes, never knowing that their beautiful green wallpaper was releasing toxic gases or that their medicine cabinet contained enough poison to kill a horse.

The Human Cost

Statistics from the period paint a grim picture. Arsenic was implicated in 186 out of 555 poison-related deaths in just one year, and those were only the cases where arsenic was identified as the cause. Many more deaths were likely attributed to “gastric fever” or other common ailments that masked arsenic poisoning symptoms.

The tragedy wasn’t just in the deaths, but in the casual acceptance of pharmaceutical incompetence. Families trusted their local druggist with their most precious possession—their health—and received poison in return. Children died because adults couldn’t tell the difference between medicine and murder.

Legacy of a Poisoned Century

The Victorian arsenic scandals didn’t just kill hundreds of people—they fundamentally changed how society thinks about pharmaceutical safety and regulation.

The Price of Unregulated Medicine

The Bradford poisoning and similar disasters served as stark reminders that in medicine, good intentions aren’t enough. The pharmacy assistant who grabbed the wrong barrel wasn’t evil—he was ignorant, working in a system that prioritized convenience over safety and trusted individual judgment over institutional oversight.

Modern pharmaceutical regulation, with its elaborate testing protocols, quality control measures, and safety monitoring systems, exists largely because of tragedies like Bradford. Every clinical trial, every drug safety warning, and every pharmacy inspection represents a lesson learned from someone’s suffering.

The victims of Victorian pharmacy disasters died because they trusted their medicine to heal them. Their deaths helped create a system where that trust is backed by science, regulation, and accountability—a legacy written in blood but one that has saved countless lives in the century and a half since Victorian pharmacists played Russian roulette with poison.

The Enduring Questions

The Bradford disaster and other Victorian pharmacy scandals raise questions that remain relevant today: How do we balance innovation with safety? What level of regulation is appropriate for potentially dangerous substances? How do we hold individuals and institutions accountable for public health?

These weren’t abstract policy questions for the families of Bradford—they were matters of life and death. The 20 people who died from arsenic-laced sweets paid the ultimate price for a society’s failure to prioritize safety over profit, regulation over convenience.

Their story serves as a powerful reminder that public health protections don’t emerge naturally from market forces—they must be fought for, legislated, and vigilantly maintained. In our modern world of complex pharmaceuticals and global supply chains, the lessons of Victorian Britain’s poisoned century remain as relevant as ever.