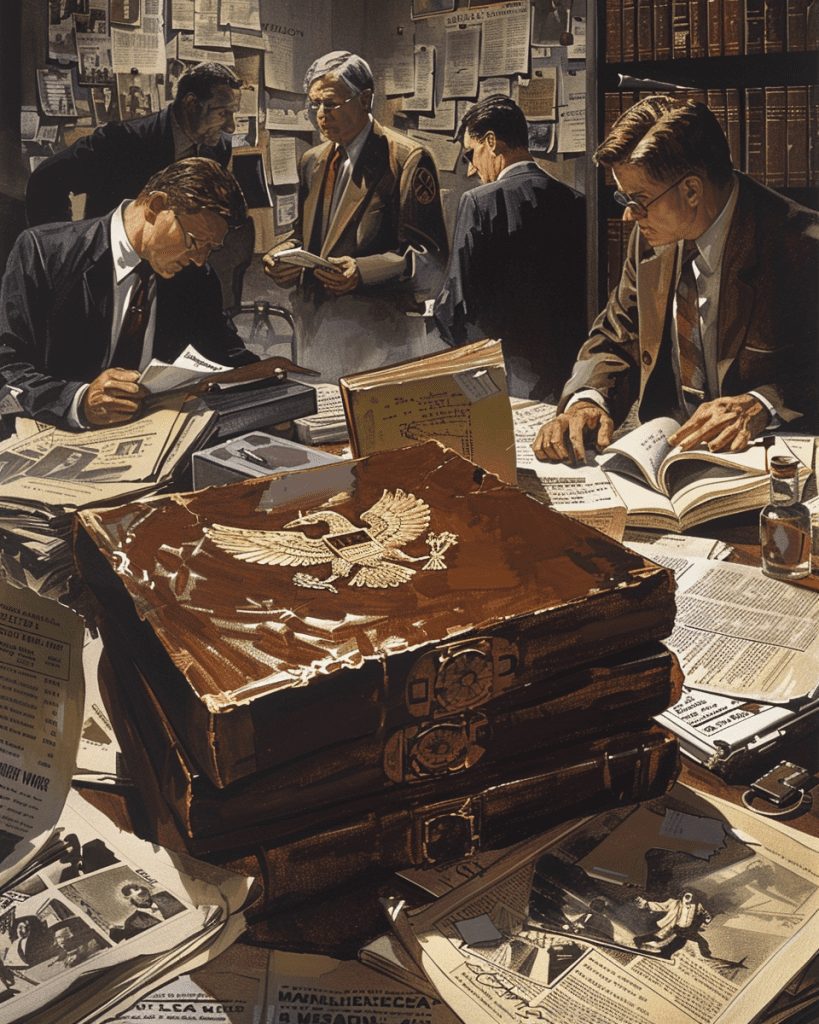

The Hitler Diaries scandal rocked the journalism world in 1983. German magazine Stern believed it had acquired a groundbreaking historical find – 60 volumes of diaries supposedly written by Adolf Hitler himself. The publication paid 9.3 million Deutsche Marks for the documents, equivalent to approximately $11.6 million in today’s US dollars.

The diaries were actually an elaborate forgery created by Konrad Kujau, who posed as an antique dealer named Konrad Fischer. Kujau had previously forged and sold paintings attributed to Hitler. His diary hoax fooled not only Stern’s editors but also several historians and handwriting experts initially consulted.

The scandal came to light shortly after Stern began publishing excerpts of the fake diaries.

Careful examination revealed inconsistencies in the paper, ink, and content of the volumes. The revelation of the fraud embarrassed Stern and other media outlets involved, exposing vulnerabilities in fact-checking processes and the allure of sensational historical discoveries.

Background of the Hitler Diaries Scandal

The Hitler Diaries scandal of 1983 rocked the publishing world and exposed vulnerabilities in historical authentication processes. It involved forged diaries purportedly written by Adolf Hitler, which fooled experts and media organizations before being exposed as fake.

Historical Context

In the early 1980s, public fascination with Nazi Germany and World War II remained strong. This interest created a market for new historical revelations.

The German magazine Stern acquired what they believed to be Adolf Hitler’s personal diaries, spanning from 1932 to 1945.

The diaries allegedly survived a plane crash in 1945. This crash was a real event, but the connection to Hitler’s supposed writings was fabricated. The timing seemed perfect – nearly four decades after Hitler’s death, just long enough for “hidden” documents to surface.

Key Figures Involved

Gerd Heidemann, a Stern journalist, played a central role in acquiring the diaries. He claimed to have obtained them through East German sources. Heidemann’s reputation for collecting Nazi memorabilia lent credibility to his claims.

Konrad Kujau, an art forger and dealer in Nazi memorabilia, was the actual creator of the fake diaries. He meticulously crafted 60 volumes, mimicking Hitler’s handwriting and using period-appropriate materials.

Henri Nannen, Stern’s publisher, enthusiastically supported the diaries’ publication. His eagerness for a journalistic coup led to rushed authentication processes.

Several historians, including Hugh Trevor-Roper, a respected British historian, initially authenticated the diaries. Their endorsements temporarily legitimized the forgeries before forensic analysis revealed the truth.

Discovery and Publication

The Hitler Diaries scandal began with purported findings of Adolf Hitler’s personal journals, leading to sensational media coverage. The events unfolded rapidly, captivating public attention and sparking intense debate.

Media Announcement

In April 1983, Stern announced the discovery of the Hitler diaries with great fanfare. The news created a media frenzy worldwide, and other publications, including The Sunday Times in Britain, quickly sought to secure publishing rights.

Stern began serializing the diaries, presenting them as groundbreaking historical documents. The magazine claimed the diaries would revolutionize understanding of Hitler and the Third Reich.

However, doubts about the diaries’ authenticity emerged rapidly. Skeptical historians and journalists questioned their provenance and content. Within weeks, forensic analysis revealed the diaries were forgeries, leading to one of the greatest journalistic scandals of the 20th century.

Exposure and Outcome

The Hitler Diaries scandal unraveled rapidly after its initial publication, leading to forensic analysis, legal consequences, and impacts on historical research. Experts quickly uncovered the forgery through scientific examination and historical scrutiny.

Forensic Analysis

Forensic experts played a crucial role in exposing the Hitler Diaries as a hoax. They discovered several anachronisms and inconsistencies in the materials used, including paper, ink, and binding methods that were incompatible with the alleged time period.

Chemical analysis revealed the presence of modern synthetic materials in the ink and paper. Handwriting experts also noted discrepancies between the diaries and Hitler’s known writing style.

These findings conclusively proved the documents were fabricated long after Hitler’s death, likely in the late 1970s or early 1980s.

Legal Repercussions

The fraud’s exposure led to significant legal consequences. Konrad Kujau, the forger, and Gerd Heidemann, the Stern journalist who “discovered” the diaries, were both convicted of fraud and sentenced to prison.

Stern magazine faced lawsuits from subscribers and advertisers. The publication’s reputation was severely damaged, leading to a sharp decline in readership and advertising revenue.

Several high-profile editors and journalists involved in the scandal were forced to resign, including top editors at Stern and The Times of London.

Impact on Historiography

The Hitler Diaries scandal had lasting effects on historical research and journalism. It highlighted the importance of rigorous authentication processes for historical documents.

Historians became more cautious about accepting new “discoveries” without thorough verification.

The incident emphasized the need for interdisciplinary collaboration between historians, forensic experts, and other specialists.

The scandal also led to increased scrutiny of journalistic practices, particularly in reporting on historical findings.

Many news organizations implemented stricter fact-checking protocols to prevent similar embarrassments.