The Franklin expedition of 1845 remains one of the most captivating mysteries in Arctic exploration history. Led by Sir John Franklin, two ships – HMS Erebus and HMS Terror – set sail from England with the ambitious goal of charting the Northwest Passage.

The expedition’s disappearance, along with its entire 129-member crew, sparked numerous search efforts and continues to intrigue researchers and history enthusiasts to this day.

The voyage began with high hopes in May 1845, but after the ships were last seen in July of that year, they vanished without a trace.

Over the following decades, various search expeditions uncovered clues about the fate of Franklin and his men. These discoveries included artifacts, skeletal remains, and Inuit oral histories that shed light on the expedition’s tragic end.

Recent breakthroughs have reignited interest in the Franklin expedition.

The discovery of the HMS Erebus in 2014 and HMS Terror in 2016 has provided new opportunities to study the ships and potentially uncover more details about the crew’s final days.

Ongoing research continues to piece together the puzzle of what happened to this ill-fated Arctic voyage.

Expedition Overview

The Franklin Expedition of 1845 was a British naval venture aimed at charting the Northwest Passage. Led by Sir John Franklin, it ended in tragedy with the loss of all 129 crew members. The expedition’s ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, disappeared in the Arctic, leading to numerous search efforts and enduring mysteries.

The Quest for the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage represented a coveted trade route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic. Its discovery promised significant economic advantages for Britain.

The British Admiralty had long sought to map this elusive waterway, organizing multiple expeditions throughout the 19th century.

Franklin’s expedition was tasked with navigating the final uncharted sections of the passage. This mission was seen as the culmination of decades of Arctic exploration. The journey would also serve scientific purposes, including the collection of magnetic data to aid in navigation.

Despite the risks, the potential rewards of success drove the British government to invest heavily in the venture.

The expedition was equipped with cutting-edge technology and provisions for a multi-year journey.

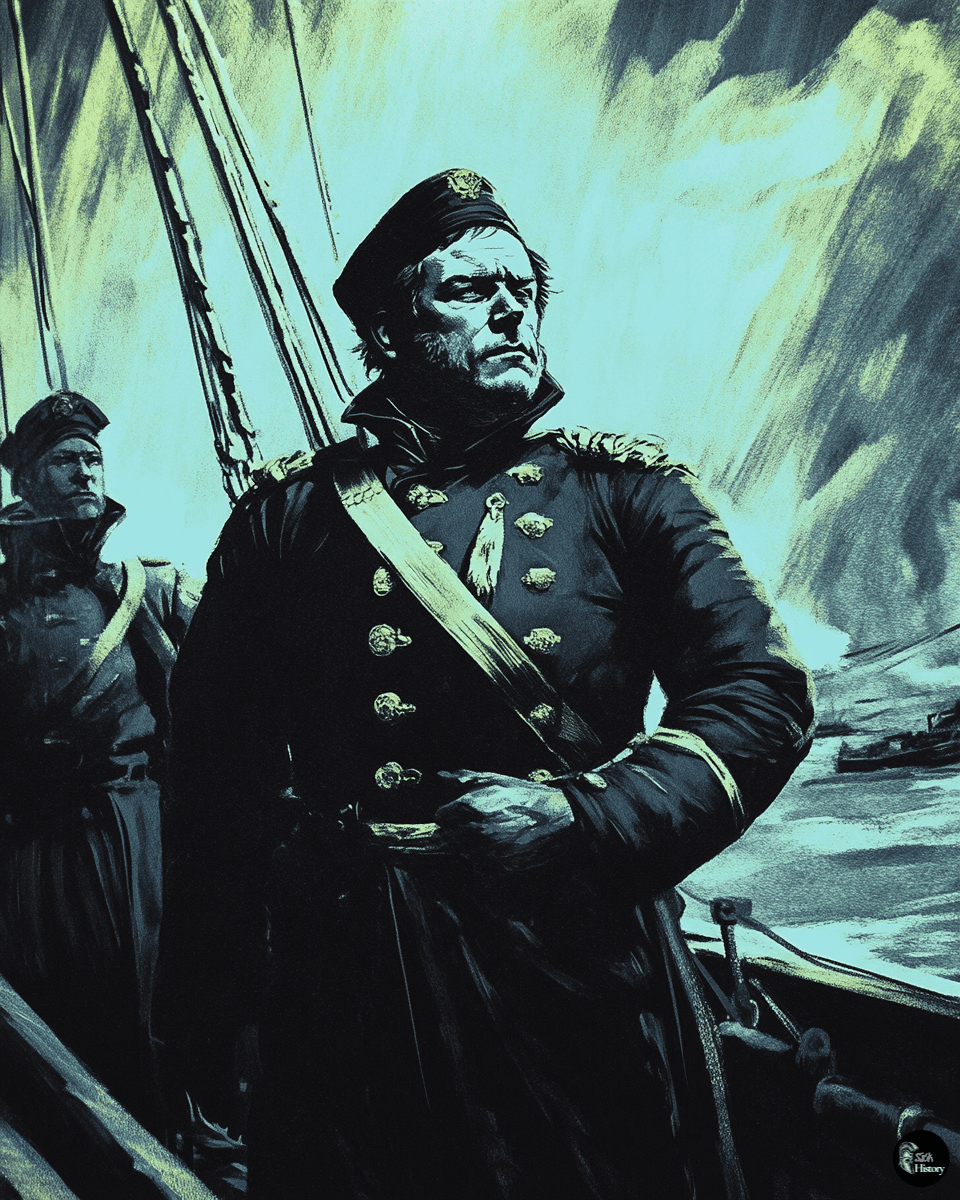

Sir John Franklin’s Role and Leadership

Sir John Franklin, an experienced Arctic explorer, was chosen to lead the expedition at the age of 59. He had previously commanded two land expeditions in the Canadian Arctic and served as lieutenant governor of Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania).

Franklin’s leadership was characterized by his extensive polar experience and naval background. He was accompanied by a crew of 128 men, including skilled officers and seasoned sailors.

The expedition’s planning was meticulous, with Franklin overseeing the selection of supplies and equipment.

Despite his experience, Franklin faced challenges in navigating the harsh Arctic environment. His decisions during the expedition remain a subject of historical debate and speculation.

Voyage Timeline and Key Events

The Franklin Expedition departed England in May 1845 and sailed north, stopping at the Whale Fish Islands near Disko Bay, Greenland, in July. This was the last time Europeans saw the expedition.

Key events:

- July 1845: Last sighting of the ships by European whalers

- Winter 1845-46: Expedition winters at Beechey Island

- September 1846: Ships become trapped in ice near King William Island

- June 11, 1847: Sir John Franklin dies

- April 22, 1848: Surviving crew abandon ships

The expedition’s fate remained unknown for years, prompting numerous search missions. In 1859, a message found on King William Island revealed the deaths of Franklin and 24 men.

Ships Erebus and Terror

HMS Erebus and HMS Terror were specially outfitted for Arctic exploration. Both ships were bomb vessels, chosen for their robust construction to withstand ice pressure. They were equipped with:

- Steam engines and screw propellers for auxiliary power

- Reinforced hulls for ice navigation

- Advanced heating systems for crew comfort

- Extensive food supplies, including canned goods

The ships were discovered in 2014 and 2016, providing new insights into the expedition’s final days. Erebus was found in relatively shallow waters off King William Island, while Terror was located in Terror Bay, further south.

Examination of the wrecks has revealed remarkably well-preserved artifacts, offering valuable archaeological evidence about the expedition’s equipment and daily life aboard the ships.

Challenges and Mysteries

The Franklin expedition faced numerous obstacles and left behind perplexing questions. Environmental factors, interactions with local Inuit, controversial survival tactics, and the long-lost ships all contributed to the expedition’s enigmatic fate.

Survival Struggles and the Role of the Environment

The Arctic’s harsh conditions posed severe challenges to Franklin’s crew.

Extreme cold and ice entrapment were constant threats. The expedition’s ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, became trapped in the ice near King William Island.

As supplies dwindled, food scarcity became a critical issue. The crew had to contend with malnutrition and the risk of starvation. Scurvy, a disease caused by vitamin C deficiency, likely afflicted many crew members.

Once the ships were abandoned, the unforgiving landscape made travel difficult. Men struggled to navigate the icy terrain, pull heavy sleds, and find shelter from brutal Arctic storms.

The Franklin Expedition Meets the Inuit

Interactions between Franklin’s crew and the local Inuit population played a crucial role in piecing together the expedition’s fate.

Inuit oral histories provided valuable information about the crew’s last sightings and the condition of the abandoned ships.

Inuit accounts described encounters with desperate, starving men. These stories helped guide later search parties to critical locations and artifacts. Some Inuit reportedly traded with crew members, exchanging food for tools and other items.

Cultural misunderstandings and language barriers may have hindered potentially life-saving collaborations between the explorers and the Inuit.

Evidence of Cannibalism and Lead Poisoning

As the expedition’s situation grew dire, evidence suggests the crew resorted to extreme measures.

Skeletal remains discovered on King William Island showed cut marks consistent with cannibalism, indicating some crew members may have eaten their deceased comrades to survive.

Lead poisoning emerged as another potential factor in the expedition’s demise. High levels of lead were found in recovered human remains. Possible sources included:

- Poorly soldered food tins

- Lead pipes in the ships’ water systems

- Lead-based paints used on the vessels

The combination of malnutrition, scurvy, and lead poisoning likely contributed to the crew’s physical and mental decline.

The Lost Ships: Discovery and Investigation

For over 150 years, the final resting places of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror remained a mystery.

In 2014, a Canadian search team finally located the wreck of HMS Erebus in the eastern Queen Maud Gulf. Two years later, HMS Terror was discovered in Terror Bay.

These discoveries sparked new investigations into the expedition’s fate.

Underwater archaeologists have explored the remarkably well-preserved wrecks, recovering artifacts and gathering data. Items found include:

- Ship’s bells

- Navigation instruments

- Personal belongings of crew members

The ships’ locations, far from where they were last reported, raise questions about how they traveled there. Ongoing research aims to unravel the vessels’ and crews’ final movements.

Legacy and Impact

The Franklin Expedition’s tragic fate left an indelible mark on polar exploration and the public imagination. Its disappearance sparked numerous search missions and advanced Arctic mapping, influencing cultural narratives for generations.

The Search Expeditions and Lady Franklin’s Advocacy

Lady Jane Franklin was pivotal in keeping her husband’s expedition in the public eye.

She financed several search missions and tirelessly lobbied for government support, leading to over 30 search expeditions between 1847 and 1859.

While failing to rescue the Franklin crew, these searches greatly expanded our knowledge of the Arctic.

Lady Franklin’s advocacy transformed the public perception of Arctic exploration. Her campaign garnered widespread sympathy and support, elevating the status of polar explorers to national heroes.

Contributions to Mapping the Canadian Arctic

The Franklin Expedition and subsequent search missions significantly advanced Arctic cartography. They filled in many blank spaces on maps of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.

Searchers discovered and named numerous islands, straits, and bays. This mapping work was crucial for later expeditions and the eventual successful navigation of the Northwest Passage.

The expedition’s fate also highlighted the importance of accurate ice charts and weather data for Arctic navigation. This realization led to improved methods of recording and predicting ice conditions in polar regions.

Cultural and Historical Significance

The Franklin Expedition captured the Victorian imagination and continues to fascinate people today. It inspired numerous books, poems, songs, and artworks.

The mystery surrounding the expedition’s fate fueled public interest in Arctic exploration, which persisted long after the initial search efforts ended.

The expedition also became a symbol of British naval might and scientific ambition. It represented both the triumphs and perils of 19th-century polar exploration.

In recent years, the discovery of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror has reignited interest in the expedition. These finds have provided new insights into the final days of Franklin and his crew.

Advances in Polar Exploration Technology

The Franklin Expedition’s disappearance spurred technological innovations in Arctic exploration.

Subsequent expeditions developed improved cold-weather gear, more efficient sleds, and better food preservation techniques.

Naval technology also advanced. Ships were reinforced to better withstand ice pressure, and new ice-breaking designs were developed, allowing for safer navigation in polar waters.

Communication methods improved with the introduction of message cairns and standardized search protocols. These innovations increased the chances of survival and rescue for future Arctic expeditions.

Archaeological Findings

Archaeological investigations have yielded crucial insights into the fate of the Franklin expedition. Discoveries span multiple sites, including Beechey Island, King William Island, and the wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror.

Beechey Island Artefacts and Grave Sites

Beechey Island served as the expedition’s first winter camp in 1845-46.

Three graves belonging to John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine were discovered there.

Exhumations revealed well-preserved bodies due to the permafrost.

Artifacts found on Beechey Island include:

- Hundreds of food cans

- Clothing remnants

- Personal items like combs and buttons

These findings provided valuable information about the expedition’s supplies and daily life during their first winter in the Arctic.

Skeletal and Human Remains Analysis

Skeletal remains found on King William Island have been subject to extensive analysis.

Key findings include:

- There is evidence of cut marks on some bones, suggesting cannibalism among crew members

- High levels of lead in bone and hair samples, indicating potential lead poisoning

- Signs of scurvy and tuberculosis in some remains

DNA analysis has helped identify some individuals, providing closure to descendants and enhancing our understanding of the crew’s fate.

Artifacts Recovery from HMS Erebus and HMS Terror

The discovery of HMS Erebus in 2014 and HMS Terror in 2016 marked significant breakthroughs.

Underwater excavations have yielded numerous artifacts, including:

- Officers’ epaulettes

- Ceramic dishes and utensils

- Scientific instruments

- Personal items like a hairbrush and medicine bottles

These artifacts provide insights into shipboard life and the expedition’s scientific goals.

The ships’ remarkably well-preserved state, including intact cabins and storage areas, offers a unique window into 19th-century polar exploration.