Every June 24th, the ancient stones of Cusco witness something extraordinary. Thousands gather in golden robes and feathered headdresses, their voices rising in Quechua prayers to a god the Spanish once tried to kill. Inti Raymi – the Festival of the Sun – transforms Peru’s former Inca capital into a spectacular theater of resurrection.

This isn’t just pageantry. It’s one of history’s greatest cultural comebacks, a celebration that survived centuries of suppression to become South America’s most magnificent festival. What the conquistadors couldn’t destroy, modern Peru has resurrected with breathtaking authenticity.

When the Spanish Tried to Kill the Sun

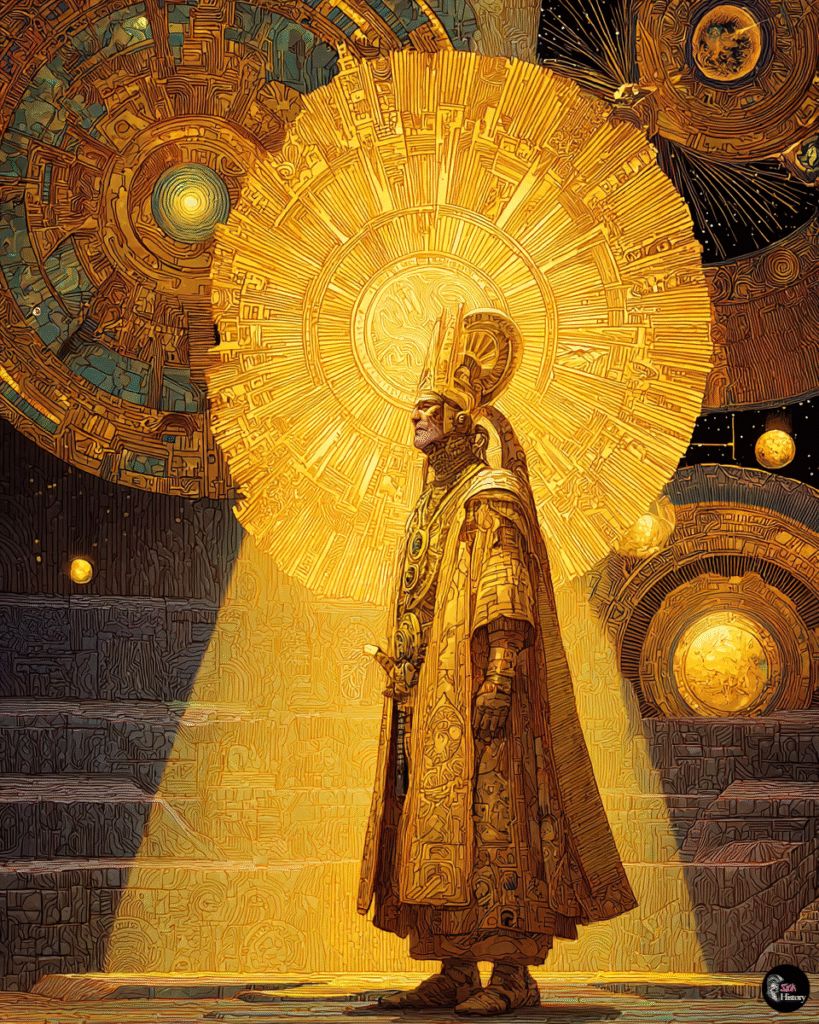

The original Inti Raymi wasn’t a quaint cultural display – it was the beating heart of an empire. Established by Pachacutec, the first Inca emperor, this nine-day festival marked the winter solstice when the sun god Inti began his journey back to full strength.

Empire’s Greatest Gathering

The ceremony transformed Cusco’s main plaza into a cosmic theater. Gold and silver ceremonial objects caught the sun’s rays like mirrors, while the Sapa Inca led thousands in prayers and offerings. Nobles traveled from across the empire, carrying precious gifts and participating in ritual dances that reinforced the emperor’s divine authority as the sun’s earthly son.

But in 1535, Spanish conquistadors decided this magnificent display posed too great a threat to their new Catholic order. They banned Inti Raymi outright, viewing it as dangerous pagan heresy that could unite indigenous resistance.

Four Centuries in the Shadows

The festival didn’t simply vanish – it went underground. For four hundred years, elements of the celebration survived in secret ceremonies and whispered traditions. Then in 1944, something remarkable happened: Peru officially revived the festival as a historical reenactment based on colonial chronicles.

The modern celebration occurs annually on June 24th at the imposing Sacsayhuamán fortress, where ancient stones witness the resurrection of traditions the Spanish thought they’d killed forever.

Sacred Theater of the Sun

Today’s Inti Raymi blends historical authenticity with theatrical spectacle, creating ceremonies that honor both ancient traditions and modern Peru’s cultural identity. Unlike other civilizations that practiced bloody sacrificial rituals, the Incas focused their solar worship on offerings of gold, coca, and chicha.

Dressing for the Gods

The preparation alone is breathtaking. The actor portraying the Sapa Inca wears a golden tunic adorned with precious stones, a massive sun disk across his chest, and the mascapaicha – the royal red fringe that once marked divine rulership. Noble participants don colorful unkus decorated with geometric patterns, while women wear long anacu dresses complemented by ornate lliclla shawls.

Every ceremonial object carries meaning: golden staffs represent solar power, ritual knives symbolize sacrifice, and vessels filled with chicha (corn beer) serve as offerings to both Inti and Pachamama, Mother Earth herself.

The Three-Act Sacred Drama

The ceremony unfolds across three locations in a carefully choreographed sequence. It begins at Qoricancha, the ancient Temple of the Sun, where the Sapa Inca leads morning prayers. Priests perform sacred rituals involving coca leaf readings – divination practices that connect the earthly realm to cosmic forces.

The procession then moves to Plaza de Armas, where the Inca delivers speeches in Quechua to thousands of gathered spectators. The celebration culminates at Sacsayhuamán fortress with symbolic sacrifices and offerings to the four corners of Tawantinsuyu, the ancient Inca Empire.

Music That Echoes Through Time

Traditional Andean instruments create the ceremony’s sonic foundation. Pututos (ceremonial horns) announce ritual moments, antaras (pan flutes) carry haunting melodies, and drums maintain rhythms passed down through generations. Each song tells specific stories of Inca mythology and history.

Dancers move in precise formations while wearing masks representing animals and spirits. They carry flags and staffs symbolizing the empire’s four regions, their choreography translating ancient oral traditions into living movement. Like other cultures that developed complex rituals – from sacred bread ceremonies to finger-cutting rituals – the Incas understood that physical performance could carry spiritual meaning across centuries.

The Sun God’s Enduring Power

Inti wasn’t just another deity in the Inca pantheon – he was the source of all life, power, and imperial authority. The festival’s symbolism runs deeper than spectacular costumes and choreographed ceremonies.

Solar Divinity in Gold

The Incas believed Inti provided warmth, light, and fertility to their mountain realm. During Inti Raymi, participants perform specific movements that mirror the sun’s daily journey across the sky, creating a direct communion between human and divine.

Sacred objects reflect this solar obsession: golden artifacts represent Inti’s radiance, while corn offerings symbolize the life-sustaining crops he nurtures. Every ritual element connects earthly existence to cosmic forces.

Cultural DNA in Action

Modern Inti Raymi serves as more than historical theater – it’s a vital cultural touchstone that connects contemporary Peruvians to their ancestral heritage. The celebration reinforces communal bonds through shared ritual participation, creating collective identity that transcends individual experience.

Traditional costumes, music, and dance preserve ancient artistic expressions that might otherwise vanish. Each color, rhythm, and movement carries specific meaning, from ceremonial garment patterns to ritual drum beats. Some cultures developed elaborate body modification ceremonies like Balinese tooth filing, showing how deeply ritual practices shaped ancient societies.

When the Ancient Meets the Modern

Contemporary Inti Raymi balances historical authenticity with practical necessities, creating a festival that honors the past while serving present-day Peru’s cultural and economic needs.

Three Stages of Solar Celebration

The June 24th festival unfolds across Cusco’s most sacred spaces in a specific sequence. Morning ceremonies at Qoricancha temple establish the ritual foundation. The procession to Plaza de Armas allows thousands of spectators to witness the Sapa Inca’s speeches and ceremonial displays.

The grand finale at Sacsayhuamán fortress becomes pure spectacle, with more than 500 actors performing in historically accurate costumes representing different ranks and regions of the ancient empire.

Organized Revival

The Municipality of Cusco oversees the festival’s organization, working with cultural preservation experts to maintain authenticity while accommodating modern crowds. Local indigenous communities play vital roles in preserving traditional elements, ensuring the celebration honors genuine cultural practices rather than creating hollow tourist entertainment.

The chosen actor portraying the Sapa Inca leads ceremonies with gravity befitting his divine role, while high priests conduct sacred rituals that connect participants to Inti’s power. Unlike some historical mass gatherings that spiraled into chaos – such as the dancing plague of 1518 – Inti Raymi maintains its sacred character through careful organization and cultural respect.

What began as colonial suppression became cultural resurrection. The sun god’s spectacular had returned, proving that some traditions burn too bright to extinguish.