In the grand tapestry of human history, few threads have been as influential yet as overlooked as the role of domesticated animals in shaping the destiny of entire civilizations. This is the tale of how the humble farm animal became an unwitting architect of global conquest and demographic upheaval.

The Eurasian Melting Pot: A Breeding Ground for Pathogens

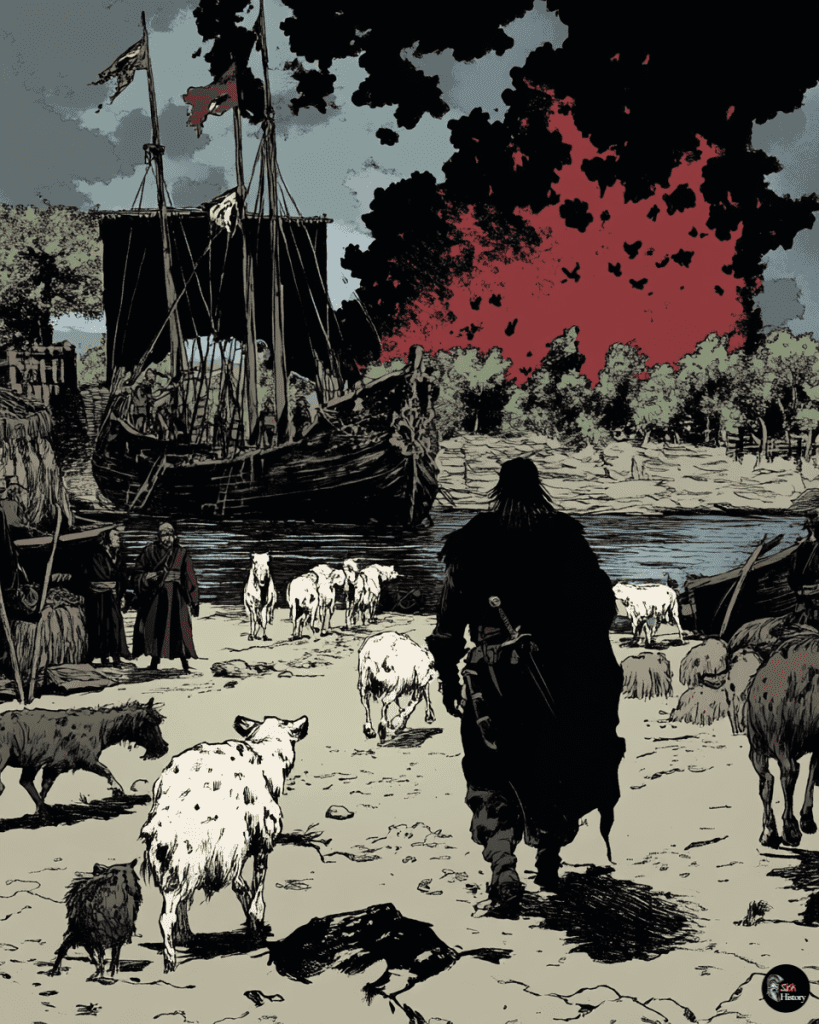

Picture the vast steppes of Eurasia, teeming with herds of cattle, sheep, and horses. For millennia, these animals lived in close proximity to humans, creating a perfect petri dish for the evolution of infectious diseases. As humans domesticated these creatures, they unknowingly entered into a dangerous dance with microscopic foes.

Viruses and bacteria found ample opportunity to jump from animal to human in the crowded barnyards and pastures of Europe and Asia. With each leap, these pathogens adapted, becoming more adept at infecting human hosts. The result? A veritable arsenal of diseases that would eventually reshape the world.

The Americas: A Land of Isolation

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, a different story was unfolding. The Americas, isolated from the Old World, had a vastly different menagerie of domesticated animals. Alpacas and llamas, the only true herd animals of the New World, were confined to the Andean highlands. Unlike their Eurasian counterparts, these animals hadn’t lived in vast herds before domestication, limiting the opportunities for diseases to emerge.

The rest of the Americas made do with a smattering of smaller creatures – guinea pigs, turkeys, and dogs. While these animals certainly played crucial roles in Native American societies, they didn’t create the same melting pot of diseases that characterized the Old World.

The Fateful Encounter

Fast-forward to 1492. As European ships touched the shores of the Americas, they carried more than just dreams of gold and glory. In their holds and on their bodies, these explorers brought an invisible army of pathogens—the products of millennia of close contact with domesticated animals.

The result was catastrophic. Native American populations, never exposed to these Old World diseases, had no immunity. Smallpox, measles, and influenza swept through the continent like wildfire. Entire civilizations crumbled, with population declines reaching a staggering 90% in some areas within a century.

The One-Way Street of Contagion

Curiously, this exchange of diseases was almost entirely one-sided. Despite the high population densities in places like Tenochtitlan and Cusco, the Americas had few infectious diseases to offer in return. The lone exception? Syphilis, which some historians believe originated in the New World.

This imbalance in disease exposure played a crucial role in the European conquest of the Americas. While Native Americans succumbed to unfamiliar pathogens, Europeans remained relatively unscathed by New World diseases.

The Long Shadow of Domestication

The story of how domesticated animals shaped the fate of continents serves as a powerful reminder of the unforeseen consequences of human innovation. The Neolithic Revolution, which saw the widespread adoption of agriculture and animal husbandry, didn’t just change how humans obtained food – it fundamentally altered our relationship with the microbial world.

In Eurasia, this led to centuries of epidemics, but also to the development of stronger immune systems. In the Americas, the absence of such diseases meant that when Old World pathogens finally arrived, the results were devastating.

As we reflect on this chapter of history, we’re reminded of the complex interplay between human societies, the animals we domesticate, and the invisible world of microbes. It’s a stark illustration of how seemingly small differences – in this case, the types of animals available for domestication – can have world-altering consequences.

In our modern, globalized world, where diseases can spread across continents in a matter of days, understanding this history is more crucial than ever. It reminds us of the delicate balance between humans, animals, and microbes – a balance that continues to shape our world in ways we’re only beginning to understand.