The Spanish Inquisition, established in 1478, was a powerful institution aimed at maintaining Catholic orthodoxy in Spain. Inquisitors, authorized by the Catholic monarchs, sought to root out heresy and ensure religious conformity.

Their methods often involved harsh interrogation techniques and torture to extract confessions from suspected heretics.

Torture was a central tool used by inquisitors to obtain confessions from those accused of heresy, including suspected practitioners of Judaism and other non-Catholic faiths.

The rack and water torture were among the cruel methods employed to coerce confessions.

Victims would endure excruciating pain as their bodies were stretched or forced to ingest large quantities of water.

The role of the torturer was to inflict physical and psychological suffering on the accused until they confessed.

Many innocent people falsely admitted to heresy under extreme duress, believing it was the only way to end their torment.

This dark period in history serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked religious and political power.

Historical Context of the Inquisition

The Inquisition emerged as a powerful institution aimed at maintaining religious orthodoxy. It employed various methods, including torture and forced confessions, to combat heresy and preserve Catholic dominance.

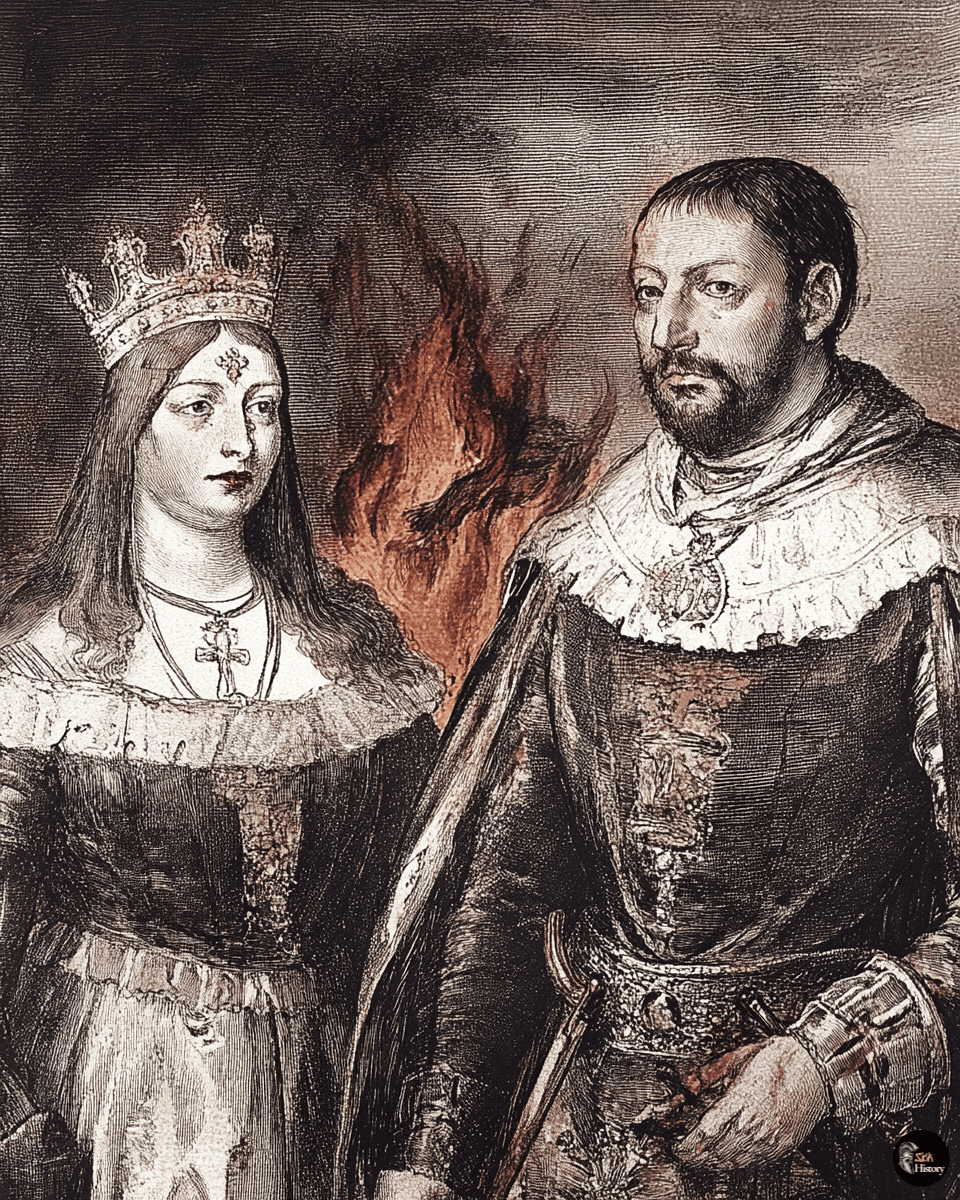

Origins of the Spanish Inquisition

The Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478 by Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II and Isabella I. Its primary goal was to ensure the orthodoxy of converts from Judaism and Islam.

The monarchs feared that some converts were secretly practicing their former faiths.

Torquemada was named Inquisitor General and set up courts across Spain.

The Inquisition quickly gained power and influence, becoming a tool for political and social control.

The institution spread to other Spanish territories, including parts of Italy and the Americas. It operated for over 350 years before being abolished in 1834.

Heresy and Its Definition

Heresy, in the context of the Inquisition, referred to beliefs or practices that contradicted Catholic doctrine. The Church viewed heretics as a threat to religious unity and social order.

Common forms of heresy included:

- Protestantism (especially Lutheranism)

- Crypto-Judaism

- Crypto-Islam

- Witchcraft

- Blasphemy

The Inquisition focused its efforts on these perceived threats, with 84% of torture cases involving accusations of Lutheranism, Judaism, or Islam.

Role of Confession in Inquisitions

Confession played a central role in Inquisition proceedings. Inquisitors viewed it as crucial for saving the soul of the accused and maintaining religious purity.

The primary goal of inquisitorial torture was interrogational, not confessional as often believed.

Torture was used as a means to extract information rather than force confessions.

Inquisitors followed strict protocols for obtaining confessions. These included:

- Multiple opportunities for voluntary confession

- Gradual escalation of pressure

- Limits on torture duration and severity

Judaism During the Inquisition

The Spanish Inquisition severely impacted Jewish communities. Many Jews converted to Christianity to avoid persecution, becoming known as conversos.

The Inquisition suspected many conversos of secretly practicing Judaism. This led to widespread investigations and trials.

Key events affecting Jews during the Inquisition:

- 1492: Expulsion of Jews from Spain

- Creation of limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) laws

- Establishment of Jewish ghettos in some areas

The Inquisition’s actions resulted in a significant decline of Jewish population and culture in Spain and its territories.

Mechanisms and Rationale

The Spanish Inquisition employed a complex system of personnel, procedures, and practices to identify and prosecute heretics.

Inquisitors wielded significant authority, overseeing interrogations that often involved torture to extract confessions.

Specialized torturers carried out physical punishments, while methods for determining heresy evolved over time.

Inquisitors: Appointment and Authority

Inquisitors were typically appointed by the Grand Inquisitor or regional tribunals. They possessed extensive powers to investigate, interrogate, and judge suspected heretics. These officials often had backgrounds in canon law or theology.

Inquisitors could summon individuals for questioning, order arrests, and confiscate property.

Their authority extended beyond the Church, with secular rulers required to support their activities.

The position of inquisitor carried significant prestige and influence. Some viewed their role as defenders of the faith, while others saw opportunities for personal gain or advancement.

Dynamics of Interrogation and Confession

Interrogations followed a structured process designed to elicit confessions.

Inquisitors employed psychological tactics, including isolation and sleep deprivation, to weaken suspects’ resolve.

Questions were often leading or repetitive, aiming to trap individuals into contradictory statements.

The accused faced immense pressure to confess, as denial could lead to torture or execution.

Confessions obtained under torture were considered valid, though some inquisitors recognized their unreliability.

Many suspects confessed to avoid further suffering, even if innocent.

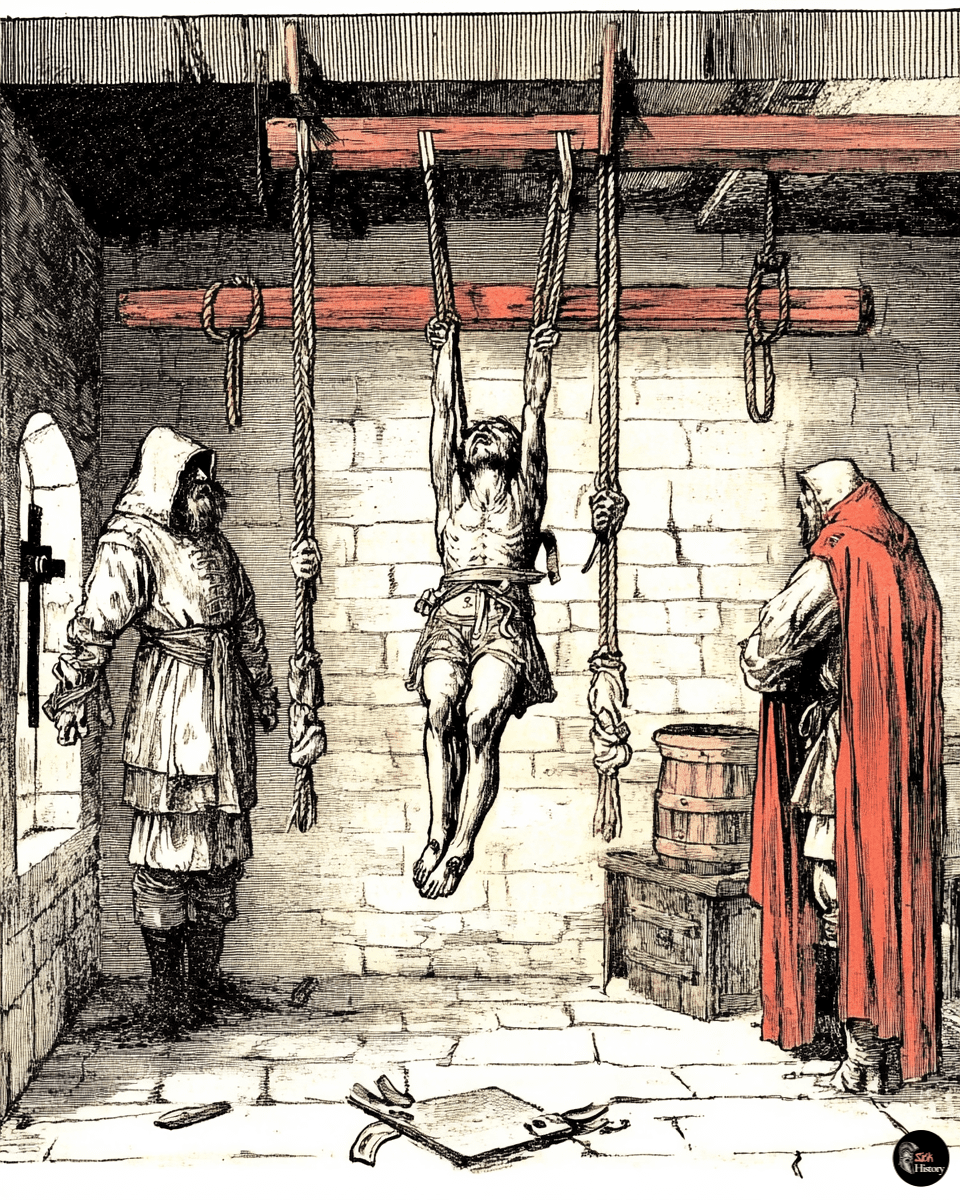

Torturer’s Function and Methods

Torturers played a crucial role in the Inquisition’s machinery. These individuals were often skilled in inflicting pain without causing death, as killing the accused was prohibited.

Common torture methods included:

- Strappado: Suspending victims by their arms, causing dislocation

- Waterboarding: Simulating drowning to induce panic

- Rack: Stretching the body to cause joint damage

Torture sessions produced horrific sounds as joints and bones cracked, serving to intimidate other prisoners.

Torturers maintained detailed records of their sessions, which were used in legal proceedings.

Determining and Dealing with Heretics

Inquisitors used various criteria to identify heretics, including witness testimonies, possession of forbidden books, and suspicious behaviors.

Judaizing Christians and crypto-Muslims were frequent targets.

The Inquisition focused heavily on prosecuting those accused of practicing Judaism, Islam, or Protestantism in secret.

Penalties for convicted heretics ranged from public penance to execution, depending on the severity of the offense and willingness to recant.

Some found reconciliation with the Church possible, though it often involved humiliating public rituals and a loss of social standing.

Unrepentant heretics faced harsh punishments, including burning at the stake during public spectacles called autos-da-fé.